Why culture got worse after the 00s, #2

Part 2: beyond narrative

The five main, causal forces behind the decline in culture are:

Capitalism revealing our preferences.

Build-up effects (new hypothesis, I’ll explain this).

Faster iterations of news cycles, cultural cycles, and social discourse.

Literature becoming less relevant, both in terms of creation and readership.

Loss of faith in definitive and long-term vision.

When people talk about the convergent culture of monochrome and minimalism — whether in logos, cars, interiors, clothes, or designs — the blame is often levied at “algorithms” shaping our preferences and making all companies do the same thing. Ignoring definition games about what constitutes an algorithm, computational models are clearly not to blame for the convergent culture.

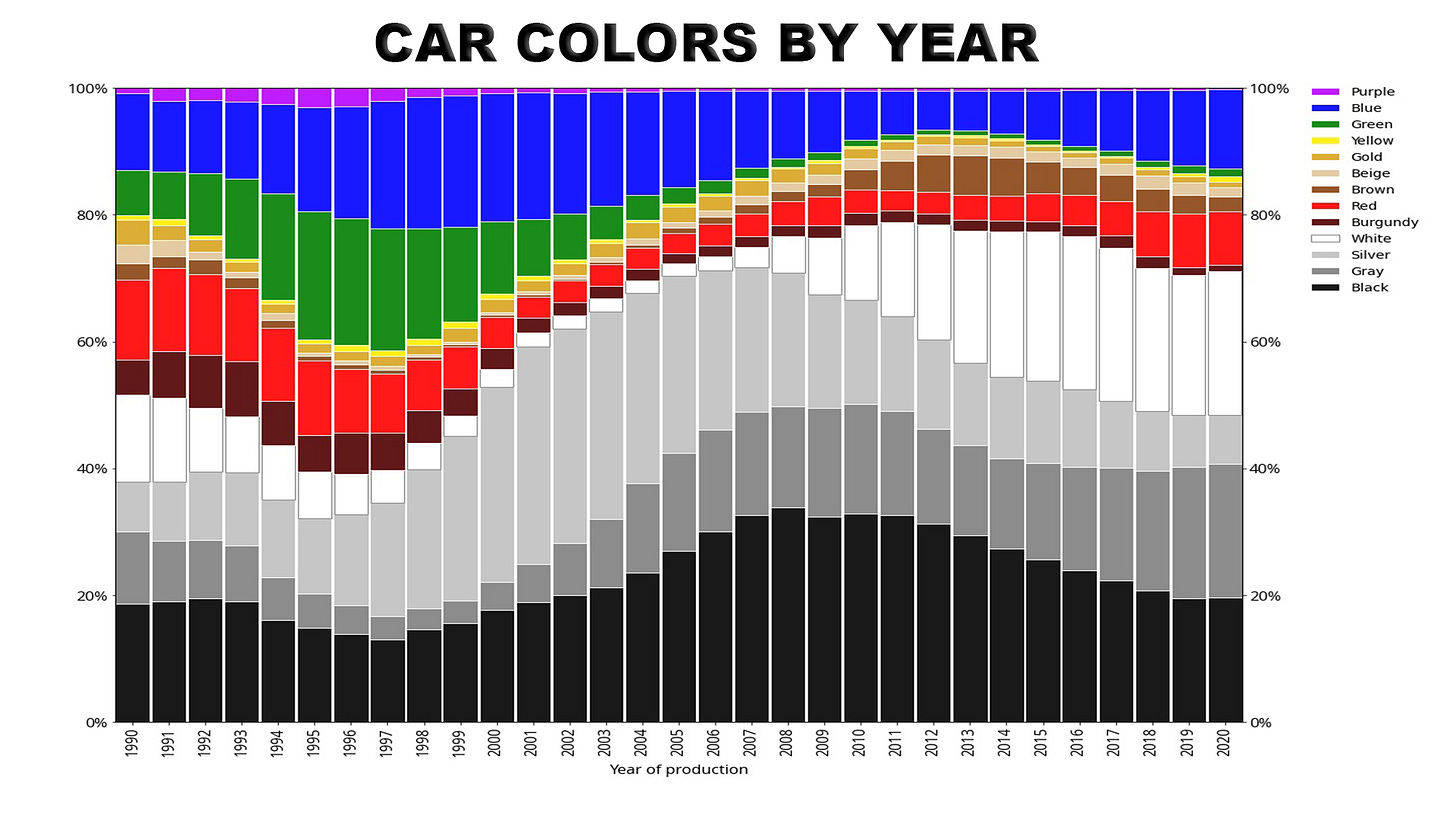

Take, for example, the change in car colours over time:

The change starts in 1998, before the big data revolution.

How about photos of artifacts in museums?

Constant increase in monochrome and colder colours ever since the 1800s. It seems more reasp, a type of artificial intelligence that assigns incentives and prices based on demand and conditions is a much more explanatory explanation for why culture has converged than computers.

And regardless of what mechanism drove the convergence, the drive to blame the algorithms is interesting. Essentially, what an algorithm does is that it takes a bunch of inputs and transforms them into an output. In the context of culture, this happens at various levels, but conventionally, people are talking about the taste-level. Companies release products, consumers buy them, and then companies adjust their response to the tastes of the consumers.

If so, then all that is occuring is an episode of the masses revealing their preferences. Cultural decline as perceived by an observer, not a god, or the public for that matter.

You could argue that, maybe, this is a molochian problem where the incentives at the individual level are to cater towards the average preference, but it would be better in aggregate if companies did things differently anyway. I find this doubtful, if there really was a burning desire for original television and film, then people would make it.

I think this is a fair case to be made that the problem with cars and interior design is molochian, in the sense that people want to resell their assets for high prices to people who want them — incentives encourage following safe or public preferences. I would ask why somebody wealthy enough to buy a new car and decorate their house would care about how much they sell it for; these are humans we are dealing with after all.

Architecture is a little different, Scott Alexander approached this issue and he thinks that it might have to do with the wealthy wanting to hide wealth in favour of signalling taste, and architects and designers finding the old aesthetics — symmetry, maximalism, and functionalism — too constraining. In that case, it would be appropriate to blame the tastes of the creators | elites and not the masses — most people like traditional architecture more than modern architecture.

Strangely, when we see an increase in drivers of cultural diversity — be it racial types, subcultural fragmentation, or political polarisation: we are afraid. We must manage it with bureaucracy and social fabric, or reduce it by means of limiting immigration or discourse. We don’t seem to want culture to stagnate but we also don’t want it to be diverse either.

There are people who do want different, new things, they are just in the minority, and there are not enough of them to sustain avant garde, ambitious art at scale. Especially when these people who want better things can just pivot to older content; the kind of people who want different things are also more likely to try to find it. Which leads me to my second hypothesis:

Build-up effects

This is not the same as a low hanging fruit effect. A build-up effect is an effect that arises from more fruits being picked, regardless of where they are on the tree.

The low-hanging fruit effect is a good explanation for the decline in productivity in the sciences and perhaps some constrained forms of art. I am, however, skeptical of whether this is the case for the rest of culture and particularly narrative, the form of culture I am most interested in. Most great narrative masterpieces are not low-hanging fruits1, but high-hanging ones, stories that were difficult to conceptualise and execute. Lord of the Rings, for example, took decades of worldbuilding and conception to bring to fruition.

I think that a similar, but functionally different effect is responsible for some of the slowdown in culture we seen: I call it the build-up effect.

Imagine a society with a set population of 100 million people and zero innovation, but possesses modern digital technology. 10,000 works of narrative are released every year. Every year, the number of total works ever written keeps increasing every year relative to the number of new works. Even with no technological or demographic progression, culture “stagnates” because the amount of total work the culture has produced is constantly increasing relative to new output as nothing else changes.

This also drives perception too. As time goes on, even if no sequels or remakes are published, it feels like culture is stagnating because, as time goes on, the best of it is increasingly old. In addition, more of those 10,000 works are going to be remixes, adaptations, sequels, or remakes of the old works.

The catch: this is clearly not the main driving force behind what is happening.

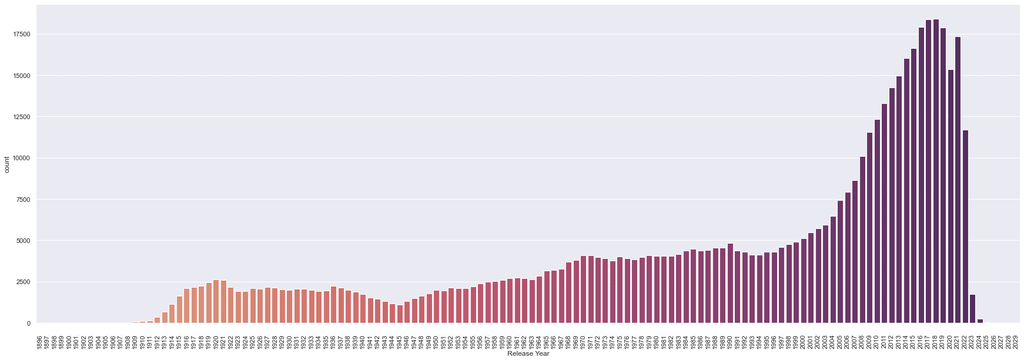

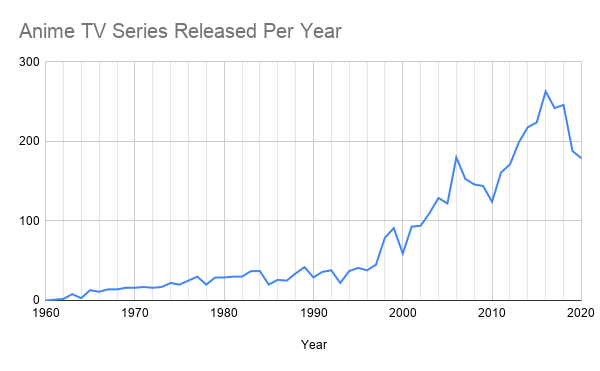

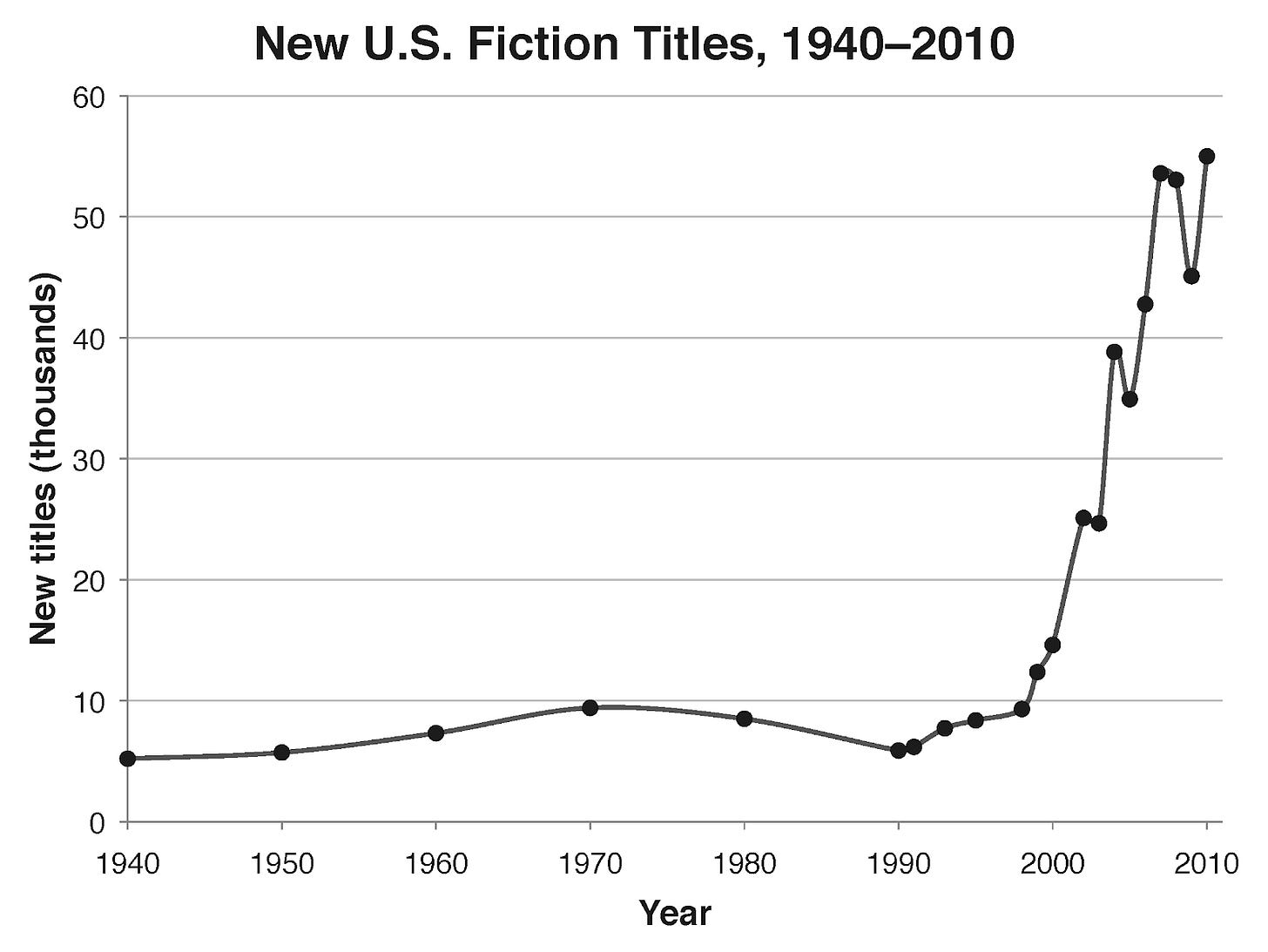

Take films, for example. The amount of new film has skyrocketed starting in the late 90s — from 5000 in 2000 to 17500 in 2020, and the same is true for other forms of art, like anime2 and books3 too.

It’s difficult to quantify the number of remakes and sequels that occur every year, because they need to be labelled manually, so people often evaluate this by looking at the top films by revenue. This will overestimate the number of sequels/reboots, as successful franchises disproportionately continue

Even so, this cannot be the cause of the problem. See the following chart: top grossing films went from 25% sequels in 2000 to 75% in 2020.

If we take these numbers at face value, then we have gone from ~3750 brand new films in 2000 to ~4300 in 2020 — an increase, in fact. The problem is that they are, well, bad.

Personally, the “sequelitis” critique of culture doesn’t land because a lot of my favourite media — Fate/Zero, Skyrim, and Devil May Cry 3 — are all sequels. I do concede, however, that this is behind a great share of the perception behind culture stagnating — not the essence, though.

I think the build-up effect, however, can explain artists not wanting to cater to divergent or “refined” tastes — those with these tastes can just look up the content they want to watch on the internet, and watch it themselves. I don’t believe true art competes with anything, because nothing can replace it, but the shift in incentives remains nonetheless.

Faster cultural iterations

Essentially, a cultural iteration is:

Ideas (e.g. mythology, political philosophy) → content (e.g. films, games) →discourse (e.g. tweets, books)→more ideas→more content

In the past, these things occurred slowly, because distribution channels took their time, attention spans were better, and the content was longer.

Now, it is extremely fast.

This speed makes discourse feel meaningful, impactful, or cool. But said speed actually makes the iterations less impactful: stable changes in conception and belief come from periods of reflection, not an attention-shifting state. I am not blaming only trashy short-form content, but also the speed up in the pace of all content, be it film, television, or books.

These fast news and event cycles give people the illusion of a rapidly changing, impactful discourse, but none of the substance: when one side starts losing face or composure, it disengages and diverts attention; the winning side claims victory, only for the “victorious” argument to be forgotten in mere weeks. The cancelled not only stay cancelled, but irrelevant too. Anti-capitalist films and television like Parasite or Squid Game go viral, disappear, only to be replaced by the enduring soul of utilitarian neoliberalism.

Growing irrelevance of literature

This was the topic of the first post on cultural decline:

I still consider the thesis defensible. I think I was too eager to claim that the best authors would turn away from writing — it’s still materially easy to do, and I think the very best, the transformational talents, are probably still there; perhaps just writing stories in different mediums.

The current mediums: video games, films, and television series, are not as suited to the creation of original and high quality content. These technological mediums serve best as vectors of transmission, not creation. Cultural changes observed elsewhere (e.g. logos, cars) cannot be explained with any of the causes I posited, besides perhaps broad technological stagnation.

Loss of faith in definition

If you look at the greatest of our species — be they artists, statesmen, philosophers, entrepreneurs, scientists — they often have different personalities or backgrounds, but there are two traits that recur:

High intelligence.

The ability to commit to a definitive, grand, long-term vision, even in the absence of financial or social rewards.

When people speak of the decline of great genuises, I think that some of it is just an artefact (might talk about this later), but I think some of it is a culture that encourages spontaneity, novelty, and “keeping options open” over planning, hard work, and delayed gratification. The former gives us consultants, financiers, polymaths, and generalists; the latter gets us to the moon.

This is a softer and less empirical explanation, but it nonetheless feels real to me. Thiel touches on this issue in Zero to One, the best book I have read to date.

The false explanations

I avoid putting people on blast. I will abide by this standard here, though it will lead to an inevitable loss in context, so I will link the posts but not mention names.

Our first theory posits that there is a general loss in divergence in human behaviour, and that this is causing the great cultural convergence: the monochrome cars, minimalist logos, and athleisure that have been panned to death, but also the lower drug use in the youth, crime reductions, and fertility declines.

The author hypothesises that this decline is driven by longer and more predictable lifespans, which encourage more risk averse behaviour and slow life strategies — less drugs, sex; more studying and reputation-guarding. Once people start doing that, their life experiences homogenise, lives narrow, and worldviews converge. This convergence in experience causes a convergence in artforms, and institutions enable this by penalising failure and documenting reputations.

I object to this analysis on almost every single level.

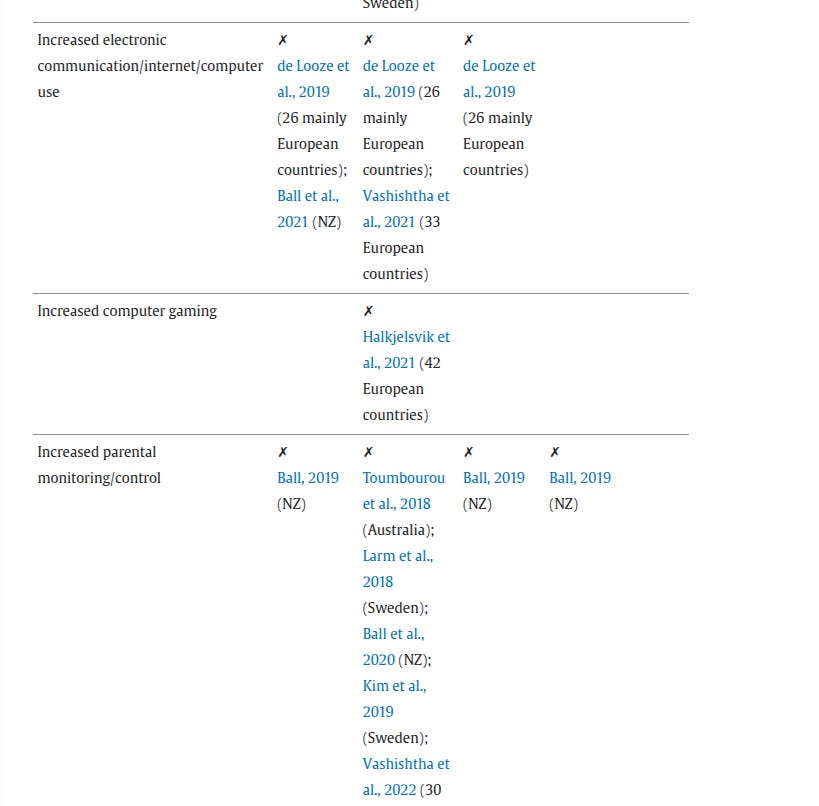

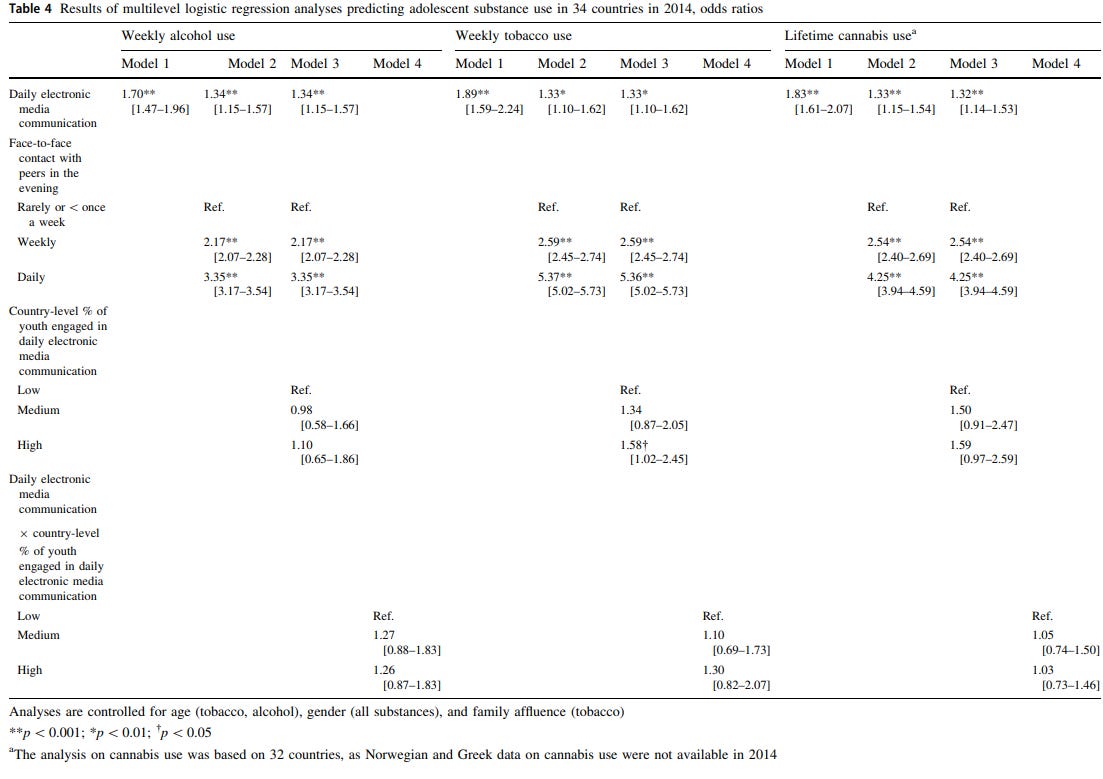

Regarding the trends in the youth, the elephant in the room is the decline in face-to-face social interaction. I ask, what kind of person spends all their time drinking alone? Smoking alone? A depressed, executively dysfunctional person. The fact that the youth of the day are turning away from the drugs and the crime is not a testament to their weakness, but to their strength and isolation. There is also statistical evidence4 that these trends we see in aggressive behaviour such as unprotected sex, drug use, and crime internationally are driven by declines in social interaction: not phones, the internet, or parents being too vigilant.

The same kinds of people who engage in petty risks — unprotected sex, violence, drug use, or crime — are actually probably less likely to create great art, which requires delaying gratification. Dysfunctional risk-takers are less risk averse, but they are also less intelligent and worse planners. It also doesn’t factor in that the kind of people who take concrete risks (MBTI sensors) are not the same type of people who take abstract risks (MBTI intuitives).

Also, just take a look at twitter, or any internet culture for that matter. Are we really getting less weird, or is people’s weirdness just getting expressed in different ways?

I also object to the cause. Longer lives and less day-to-day death risks encourage behaviours with longer time horizons — which encourage great art.

There is also another theory which states there is no cultural decline, and all of the innovation is hidden in new art forms: tiktoks, tweets, or memes. Now this is a cope.

Many of these advocates of internet culture (not the author, to be fair) never stop to tell us what about it they enjoy; I have no such reticence: I like the naruto AI parody where Naruto’s body is inhabited by an African man, the Skyrim AI parodies of American culture, RWBY fanfiction, and the Sonic fandubs with Alfred in them.

These people never do this because the new culture is, simply and obviously, worse than the old one. It’s not even trying to do the same thing, so maybe it doesn’t even make sense to say it is worse, but it doesn’t function as a replacement. Some of it might be funny or entertaining, but it’s not a substitution for masterpieces like Chinatown, Twin Peaks, or Ghost in the Shell. These creators of the new culture, no matter their popularity, either envy or admire the great artists.

There is this cope that “everybody wants to be a poaster”, that discourse matters or whatever, but real culture comes in serious art forms: anime, video games, film, and books. Any 200k+ twitter or tiktok account would 100% prefer to be making transcendent art or building monopolies than doing whatever they are creating at the moment. The issue is that these online platforms attract a certain neurotype, typically high in insecurity, drive, and disorganisation, and low in executive function and maturity; selecting them into social media and away from more wholesome forms of creation.

A third theorist posts that the world has been ruined by “dopamine seeking” devices which distract us, pacify us, and do a bunch of bad things. Zuckerberg, Musk, and the elites are to blame for all of this. No really, that’s what he thinks:

Do you remember rule two above? It said: Look to the teens, and their digital lives.

When you do that, you see immediately that they are the main victims here. This flattened culture is all they have ever known. It’s now the landscape of their inner lives.

Many of these youngsters lack the skills and tools required to escape. So this flattened world is really their prison—and the billionaire wardens (Mr. Z and Mr. M and all the rest), who get rich from their brokenness, want them held in their digital chains forever.

Now, I am not exactly the biggest fan of short form content. But I think this is the wrong line of attack — who, may I ask, is using phones to look at all this garbage?

Technology might have given us more distractions and meaningless fluff, but earlier generations had these things too, just in forms that had other ends and were delivered in a more palatable form: social interaction, exercise, collecting, television, and having sex with prostitutes. People starting projects and losing focus, lacking discipline, or the ability to delay gratification is a perennial problem.

Technology also gave us more opportunities and tools: easily pirated digital workstations, digital art software, and free platforms. Humankind, instead of being driven to creation, has decided to make cheap, stupid content or sterilise itself with it. The “intellectuals” ignore this obvious fact and divert the bad conscience to technology — the best thing humanity creates.

I will, say, on a positive note, that it seems like the mediums that are stagnating the least (video games, music) are also the ones where people have the easiest time making things on their own without the help of mass audiences, marketing, or institutions. Within music, I see many emerging styles like witch house, emo rap, lofi, or Phonk, they do not tend to hit the top of the charts, but many people still listen top them nonetheless. In that regard, it seems that our artists are doing relatively fine, it is the masses and elites that are flaundering.

Previously, I was concerned that perhaps the problem was that we are getting more content, and it has become harder for the collective intelligence to sort between all of it. Even small changes in the correlation between popularity and quality could change the quality of what rises to the top.

I no longer think this is the case. Strictly speaking, there are two barriers to the creation of culture:

The number of people who engage with a form of culture.

The ease of creating said culture.

Lots of people watch anime, but only several hundred are created per year, because creating anime requires a studio and capital. Novels aren’t read that often, but are frequently written because it is far easier to write a novel than film a movie.

The raw quantity of film and anime has increased by an order of magnitude in the last 20 years, but 17500 films have been released in 2020 and 300 anime were shipped out (not aired) that year. Those numbers also differ greatly, but I feel like the “rise to the top” effect is pretty similar in both mediums and isn’t affected that much by the raw amount of content. More coal doesn’t hide the gems if they are shiny enough.

People have also highlighted that selection in the past was different: it was institutions that chose whether a book was published or a film was released. Now, computers + social media make distribution of content much easier, which lowers the quality of content by default. This is probably true, but popularity has always been directed by word of mouth, which is deterministic at a high enough scale.

So

Finding good culture is easy. Find a computer, get on the internet, and search for it.

If so, then why does this even matter? To some people, this matters because culture matters to them beyond consumption; I can sympathise with this motivation. Alternatively, one could read discourse regarding cultural stagnation as performative, engaged in to signal “divergent” or “higher” tastes that stand above the mass culture, that you are keyed in to the latest trends and discussions on the internet.

I think the answers that some of these intellectuals give is rather telling. That the problem is the “elites”, that modern life makes us pod people that don’t want to take risks, and that that cheap husk of a culture we call “memes” is a replacement for high art. We would love to blame anybody but us, the people with the right tastes and preferences. Or maybe the problem is that I am not trying hard enough to find the right cultural critics.

In social environments, exposure to mass culture is inevitable. And here’s the thing: the point of these environments is the people, not the culture. I don’t think whether Golden by KPOP Demon Hunters being a good song changes whether I enjoy dancing to it with my 6 and 8 year old siblings.

I do think this is true for a lot of popular, mass consumption art. Harry Potter discovered the key to popularity and fan generated content — young cast, magic, good narrative, classic themes, and common location. Naruto did the same thing, but for anime.

I also think that the low hanging fruit applies to science, and maybe a few other art forms like rock music, but I’m not as sure about the last one.

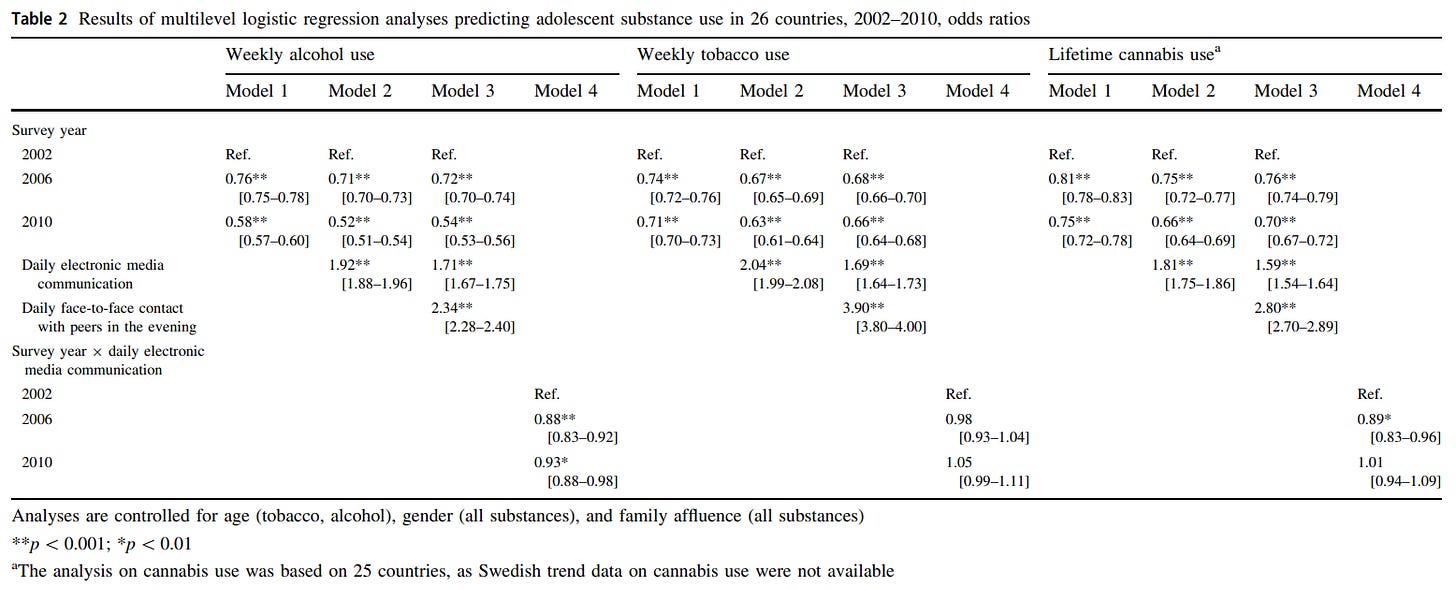

Let me look at the main source that suggests the decline is due to face to face socialising. Their regression table is pretty unambigious, extremely low p-value:

For the individual-level effects, it’s also pretty unambigious:

The record also does not suggest they are electronically driven either. See Table 1:

Some of it is also just later initiation ages, which goes against the author’s hypothesis:

My explanation for the decline in american entertainment is that most narrative art creators and all the gatekeepers have been mindkilled by politics, TDS and the Culture War.

Something like that has happened before. About 100 years ago the visual arts of painting, sculpture and architecture became dominated by leftist radicals that wrote political manifestos and who captured the key artistic institutions and pushed out the technically skilled artists (and spatially tilted) that were continuing the previous artistic tradition. The result has been a century of ugly art and misanthropic prestige architecture initially justified with marxist verbiage than by sheer institutional power. The verbally tilted used words to beat the spatially tilted out of art.

Classical music suffered a similar sad fate around the same time.

The radical innovators tried the same with literature but back then leftists couldn't gatekeep it effectively as the public kept buying the novels they liked bypassing the critics.

Funny enough ballet, the most aristocratic art form, survived because it had continued support from Lenin and Stalin with whom the "innovators" didn't had the balls to argue so ballet is one artform in which classical and modern styles are peacefully coexisting.

While the current decline in narrative arts is steep I argue that it has been going on for decades as the Overton Window of permitted artistic discourse became narrower and narrower.

The fractal, chaos, wordless anime, shortform are here.

The entertainment complex is trading dead, inaccurate hazy skeletons jammed with backstory, plot, archetypes, stereotypes dressing mythological thought.

Hollywood never recognized it was a language factory, it blankly remained mining stories, and no one wants them anymore. Problem is, no one knows what to replace them with.