Happiness research doesn't make you happy

If you want to be happy, figure it out for yourelf

Most happiness research follows this formula:

Identifying a proxy for happiness, like depression diagnoses or self-reported well-being.

Correlating said proxy with a trait.

The understood conclusion is that the observed correlation is causal and that people should find happiness by optimising for the traits that are correlated with happiness.

Sometimes the methodology is more statistically complex, allowing for a more explicitly causal interpretation, but my criticism here is not methodological or even causal.

The first problem with happiness is the concept of happiness itself, which is murky and difficult to define; often people confuse it with contentment (one’s own life evaluation), nirvana (an absence of suffering), or joy (an emotion). I define happiness as the relative balance of positive/negative emotions that occur within a context-appropriate timeframe. Concretely, if you move away from a location you dislike and start to feel more positively about your life, the context-appropriate time here is after your move.

With regard to contentment, it’s better to think your life is good than bad, but if your life is actually bad, then you should think it is bad — self-delusion will only remove the purpose of negative self-evaluation (self-transformation) and keep the pain.

This is also where I break with conventional wisdom on hedonism. Hedonism is true insomuch as your emotions are what describes your value function, but it’s false insomuch as the emotions themselves should not be optimised. Even if they really are the “ultimate goal” of everything.

Often when people criticise hedonism, they do so arguing that it is good to sacrifice pleasure for the purpose of something else, e.g. avoiding hyper-palatable food to feel healthier. In reality, the example is simply a trade which exchanges one reward for another. Typically, when people propose these examples, the compared rewards are of different natures or time scales, which makes the rebuttal seem legitimate when really it is a misunderstanding of the hedonist thesis.

The conflation of positive/negative emotions with good/bad value is also an issue. Hedonism doesn’t say that positive emotions are good or that negative emotions are bad — pain can be good and pleasure can be bad. Drugs can feel good and ruin your life. People with a congenital insensitivity to pain suffer from their disorder: unnoticed infections, self-inflicted injuries around the mouth from biting, and bone fractures.

Do people really know what they feel?

When people take surveys, they are most likely in a reflective mode and not experiencing any strong emotions, so any response they give will be regarding an assessment of their life as is and not their current emotional state. Sexual activity might bring people joy, but they do not experience said joy when they are filling out a survey and it might not even weigh into their responses.

I think that people have a decent intuitive grasp of how good their life is to live, but I question how accurate these reports are for the purposes of statistical research. The norm is that when different people evaluate different things at a subjective level, their responses do not strongly correlate — whether it’s peer reviewers or raters of personality. I see no reason why happiness should be different.

Researchers often think about happiness in poor theoretical terms; allow me to introduce the example of money and happiness. Let’s be clear here: people feel joy when they receive money. Said joy might be momentary or fleeting, but it is joy all the same. If this is the only emotional thing that money does, then money does cause happiness, just to a limited extent.

One could criticise this argument on the grounds that income statistically tracks life satisfaction more than happiness, but I defer to my criticism of how people report their emotions in these surveys: it’s completely possible that income and resources cause people to feel more positive emotions on a day-to-day basis but said increase is not registered in their resting emotional state, but is reflected in their self-reported life satisfaction.

Then there is also the question of what is done with the money. If the money spent on impulsive purchases, drugs, or other things that don’t matter, then said money is at best a neutral element and at worse a negative one. If said money is spent on things that actually matter and the purchaser consistently values, then it is at worst a neutral element and at best a positive one. Given that income is an instrumental value, it seems odd that this aspect of the debate is so under-emphasised.

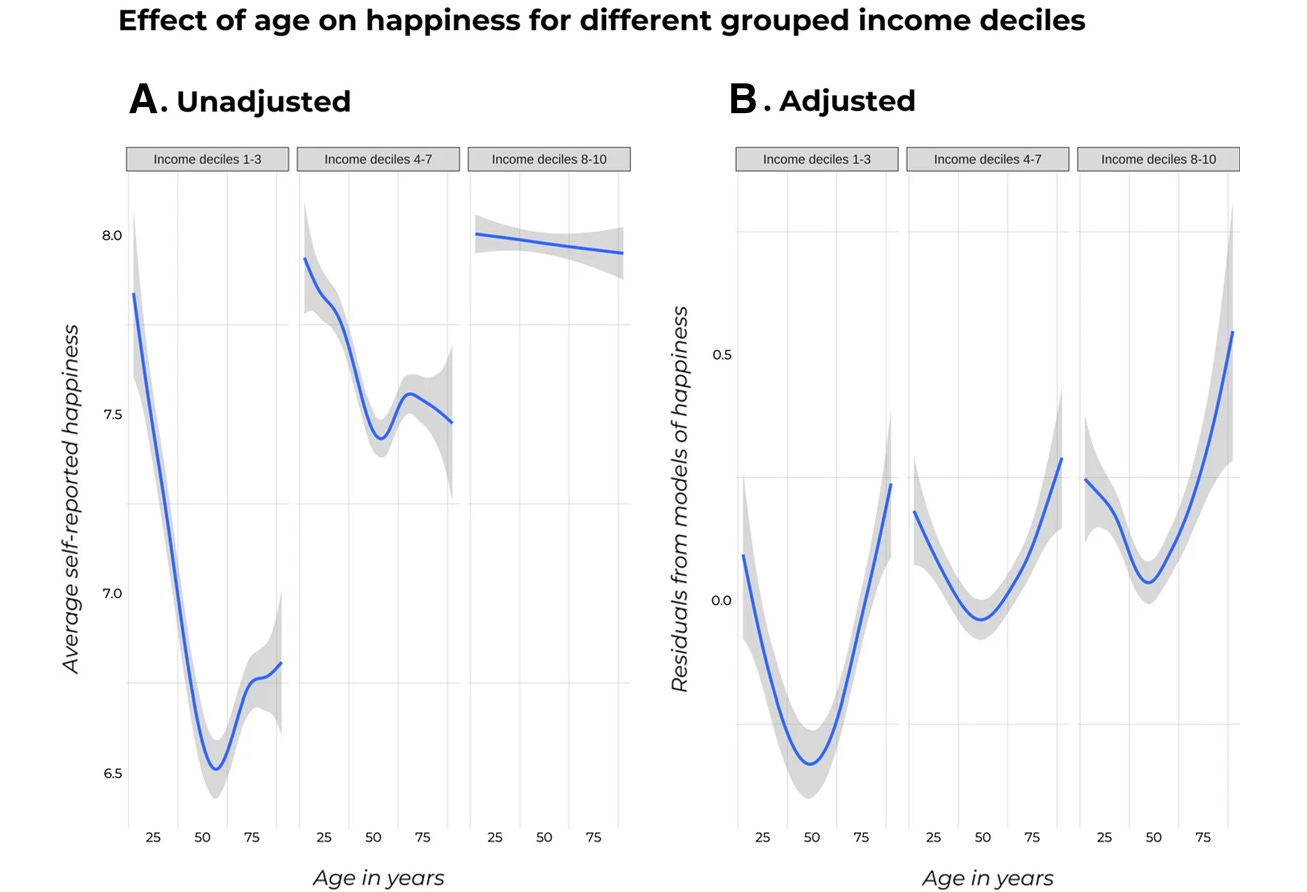

What has also been neglected is the massive age interaction that exists in the income ~ happiness association. There is little correspondence between income and happiness in the youth, but a stronger gradient emerges as people age:

My interpretation is that a lot of the appeal of a career is not the work, or the money, but the sense of progression itself. People might be fine with earning $30,000 a year while they are building up their skillset early in their career, but somebody who is making the same amount without the same trajectory will not feel the same way. Also, younger poor people might still have a chance to find a different line of work, but that chance diminishes with age.

The hedonic treadmill is real, insomuch as people feel momentary joy when they upgrade their living standards, but they return to their old resting emotional state after said improvement. I would argue this is true for literally everything that we do — everything is impermanent, as the Buddha says. Most older people I know say running on the treadmill is a bad idea, which seems credible to me, though I can’t say I know firsthand.

That aside, I doubt the reversion to the resting emotional state actually reflects the day-to-day lived experience: if we take two identical lives, and give one person high quality speakers and another low quality speakers, I wouldn’t be surprised if they claimed to experience the same level of happiness, but the fact remains that the person who has higher quality speakers is experiencing a better life, even if the degree is marginal and not subjectively observed.

People who doubt the effect income has on happiness are often well intentioned and are actually correct for the most part, insomuch as money itself doesn’t bring contentment or nirvana, and even when you look at the material aspect, it must be used competently in order to make any difference.

How do you actually find happiness?

Happiness research is poorly framed. It uncritically accepts a universalist frame by asking questions like “does exercise cause happiness?”, when the correct question to ask is “do some people value getting exercise?”.

It’s been observed that, based on meta-analyses of RCTs that control for publication bias, that randomly assigning people to do exercise does not make them less depressed. One could then wrongfully argue that exercise is a waste of time and nobody should do it, when really what should be questioned is the methodology.

In the real world, everybody is exposed to physical activity of some kind. Nothing is stopping them from engaging in it. Naturally, people who value the experience of engaging in physical activity and the rewards it brings them will gravitate towards it, while those who don’t care for them will not. These RCTs needlessly distort this environment and try to make people do things that, based on their revealed preferences, do not want to do.

Most people are overly insecure, and when they are unable or unwilling to do exercise, their bad conscience attributes it to a lack of discipline and effort, when really they might just not care for it. Because exercise is high status and socially desirable, people who would otherwise not care for it feel compelled to do it, and will delude themselves into thinking that they will be happier once they acquire the discipline and aesthetics of a fit person.

Genetics of happiness

All traits are heritable, and life satisfaction is no exception, with a heritability of 33-38%1. Some happiness researchers take that as evidence that people have genetic set points of emotion that people always regress back to when they are rewarded or when their experiences deviate from their expectations. This is not the correct interpretation.

35% is simply not a high heritability, it’s even below the heritability of income (for one year) or education. The heritability of a trait also does not imply that it is directly genetically caused. In the case of income/education, there are no genes that print out dollars or college degrees, but genes can change people’s personalities/levels of intelligence which then have an effect.

I don’t doubt that some people have an innate predisposition to positive or negative emotions, and that said predisposition affects how how they feel on a day-to-day basis. That said, it’s also possible for people to affect their extrnal environment using their own will and learn things that erase the suffering that comes with pain, counter to set point theory. Though I would admit that said ability to be introspective, active, and self-transforming is also heritable and likely unlearnable.

The focus on the “set point” and “resting emotional state” in happiness research seems rather odd in general. It’s not like you feel anything in a “resting emotional state”. Nobody does. You aren’t supposed to. What matters is the relative balance of positive to negative experiences.

It’s possible for people to be in the same situation but with different interpretations of it: one who is fine with it, another who is not and strives to go beyond it. The one who is not content might feel the negativity that comes from being in an unsatisfactory situation, but they might feel a sense of progression or struggle that comes from trying to change, which is arguably a positive phenomenon.

Another misunderstanding I see is that the genetic portion of happiness is somehow outside of your control or this implies that people can’t strive to be happier beyond a certain extent. This is also wrong: you ARE those genes. You ARE the circumstances that shaped you. That conscious “you” that you think is controlling your behaviour independent of your genes and circumstances is completely fake, but that is no reason to give up. If you are unhappy and want to change, DO IT. Don’t let philosophical debates about free will stop you.

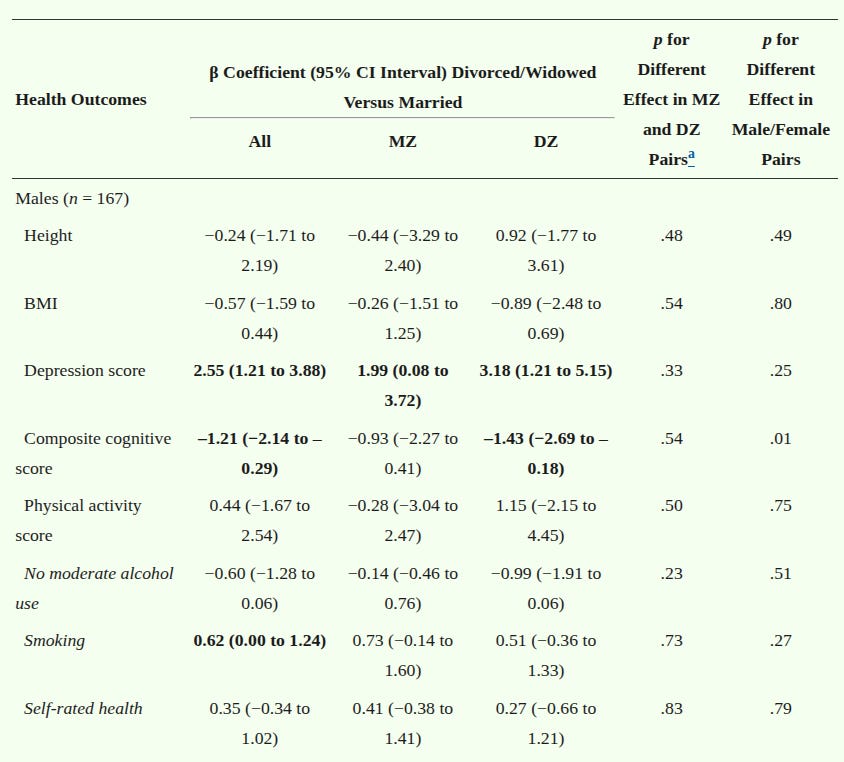

Sometimes, researchers bring out the big guns and try using twin controls: they test whether the relationship between a trait and self-reported happiness exists within MZ twins. Technically, it’s still possible for a non-causal correlation between a trait and happiness to exist within MZ twins, but the idea behind the method is that if the relationship doesn’t exist between people who share the same genes, then the relationship is due to genetic confounding.

When people test for whether the association between a supposed cause of happiness and a trait at the genetic level, it almost never exists: not for exercise, homosexuality, and social media use. Though it does for income2. I also suspect most of the supposed causes of depression like pornography, video games, promiscuity, or social isolation would yield similar nulls that we would ignore because we just want to hate degeneracy because it is degenerate.

With regards to depression, the big error I see in the literature on depression is that it assumes it is a bug and not a feature. That depression somehow must reflect a physiological cause like poor nutrition, disease, or a genetic disorder and is not something that happens to functional organisms. I see two types of people who conceive of depression this way: the anti-hedonists who mistakenly believe that you should pursue “meaning” (fake), “status” (fake), or some other higher value (probably, but not certainly, fake) instead of pleasure; then you have the hedonist relativists who don’t actually understand hedonism and think that nothing matters besides positivity, so if depression makes you feel negative, then depression is bad.

The main effect depression has on people is that it reduces their energy levels, willingness to take risks, and the joy they receive from experiences. All of these things, on a superficial level, are bad. But the underlying purpose behind all of these physiological changes is to stop them from engaging in pursuits that lead them nowhere, or inform them of what bad outcomes are.

From a mechanistic point of view, frivolous activity is likely to lead to depression, as depression is caused by doing things that are rewarding in the short term or assumed to lead to rewards, but don’t actually lead to anything in the long-term. I think it’s probably true that most people would be depressed if they played video games for 80 hours a week, but I don’t think that’s the only way people can get depressed and I also think that it’s rare for people to sustain that level of dedication.

People can also get depressed by failing at a non-frivolous activity — an unsatisfying relationship, exercise that leads to no gains or injury, a dead end job, or a friendship that ends in embers. People do actually feel something when they try to accomplish things in life, it’s not the easy pleasure of doing something like eating fast food, but a different kind of reward that comes from effort and struggle. I actually think that people failing at otherwise socially acceptable and long-termist pursuits contibute to much more to depression than the frivolty that everybody loves to scream at, though I admittedly have no evidence for this claim.

So

We don’t need surveys and statistics to find happiness. Maybe we just need to look… Inside. To see if we are happy. If we are, then we don’t need to read any studies because we are already happy. If we are unhappy, then we must find out for ourselves what is causing our unhappiness, and there is no statistic that can identify what is making any specific person miserable.

And even if research on happiness could be helpful, in its present state it is a failure due to its tacit universalism and ignorance of inconvenient null findings. The genetics research on causes of happiness and depression is interesting, and useful for the sake of polemic; even then it is either ignored or misinterpreted by the public.

Further reading:

Money does not buy much happiness — Maxim Lott. Here he cites a study that leverages data on people who are living their lives in the moment and are asked by an app how happy or unhappy they feel in the moment, which gets past some of the evaluative error observed in studies on the question. The observed effect was linear (no threshold effect) but small:

Politics is worse than video games, porn, and drugs combined — Max. Can’t link this piece enough times.

Minority Stress Model — East Hunter. In a similar vein to exercise, the link between homosexuality and mental health appears to be genetically mediated.

On my further reading lists — I often include articles that I disagree with on details or even the overall picture if they informed my thinking and consider valuable. I dislike doing disclaimers, but I assume I will be asked about this tendency at least once, so I may as well clarify myself.

Two random studies I found + the meta-analysis all converge towards roughly the same value. See:

Wellbeing is a major topic of research across several disciplines, reflecting the increasing recognition of its strong value across major domains in life. Previous twin-family studies have revealed that individual differences in wellbeing are accounted for by both genetic as well as environmental factors. A systematic literature search identified 30 twin-family studies on wellbeing or a related measure such as satisfaction with life or happiness. Review of these studies showed considerable variation in heritability estimates (ranging from 0 to 64 %), which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the genetic influences on wellbeing. For overall wellbeing twelve heritability estimates, from 10 independent studies, were meta-analyzed by computing a sample size weighted average heritability. Ten heritability estimates, derived from 9 independent samples, were used for the meta-analysis of satisfaction with life. The weighted average heritability of wellbeing, based on a sample size of 55,974 individuals, was 36 % (34-38), while the weighted average heritability for satisfaction with life was 32 % (29-35) (n = 47,750). With this result a more robust estimate of the relative influence of genetic effects on wellbeing is provided.

At a p < .01 level, so just maybe. Perhaps it does for marriage too, but the p-value for the MZ association within men is not very good though (I’m not talking about the MZ-DZ difference:

It is useful to know population effect averages, even if one's own case might be different.

So IMO it is quite useful to know that socializing and sex consistently come up in surveys as happiness-inducing.

Maybe someone is an extreme introvert, or asexual, and decides those things aren't for them. Great. But happiness research at least highlights good places to start exploring, if one feels they'd like to be happier.

Arguably this is the case with almost all research ... an RCT drug trial will tell you typical effects and maybe distributions of effects, but ultimately you have to actually try and see if the drug works for you or not.

As a side note, that's interesting and surprising that randomly-assigned exercise came up as no-effect in that meta-analysis you cite. Worth further digging on the methodology.