Does selecting employees for IQ work?

Yes, with caveats

TL;DR:

It’s not illegal in the United States.

IQ explains 25% of variance in job performance within occupations, more so for complex and technical professions. It beats out every single predictor of job performance typically used by firms for selection, besides work samples.

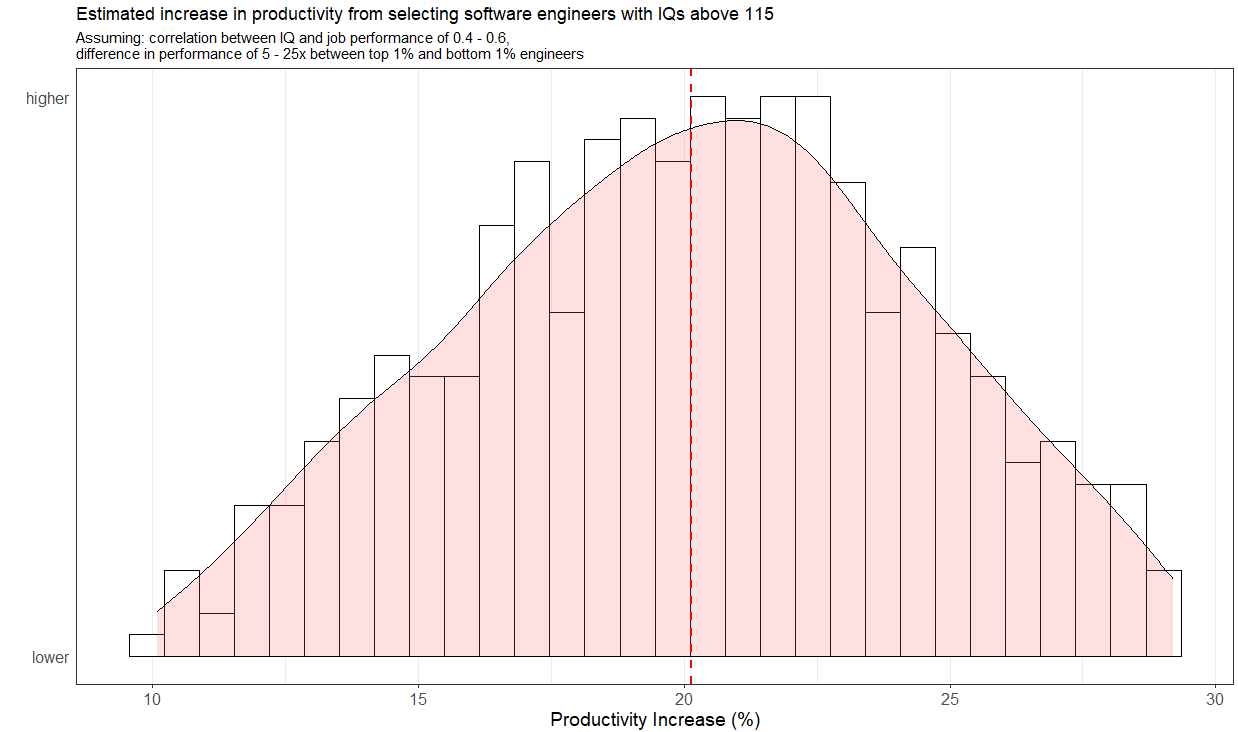

A firm that selects software engineers with >115 IQs would see a 10-30% productivity boost, which would outweight the expenses that come from selecting smarter employees.

It’s unpopular primarily due to social and practical reasons, not legal reasons.

Legality

First of all, it’s not illegal to do this in the United States. There was a supreme court case (Griggs vs Duke Power), concerning a firm that used IQ tests as a means to discriminate against black employees1. The court ruled that businesses must show that any test used for selection, if it produces ethnic group differences, is “reasonably related to the job.

This is not equivalent to making such testing illegal, especially given the empirical literature showing that more intelligence employees tend to have higher productivity. Furthermore, in a recent case (Ricci vs DeStefano, 2009), the supreme court ruled in favour of 20 firefighters who were selected for management roles based on test scores, but were rejected at the last minute due to concerns over disparate impact.

The combination of these two rulings does make it legally difficult. Firms who select for employees on the basis of IQ test scores, which contain racial differences, open themselves up to litigation if they can’t prove that said tests are relevant to the occupation2. If they discard said scores on the basis of their racial differences, they open themselves to a lawsuit which they would likely lose.

The correlation between IQ and job performance

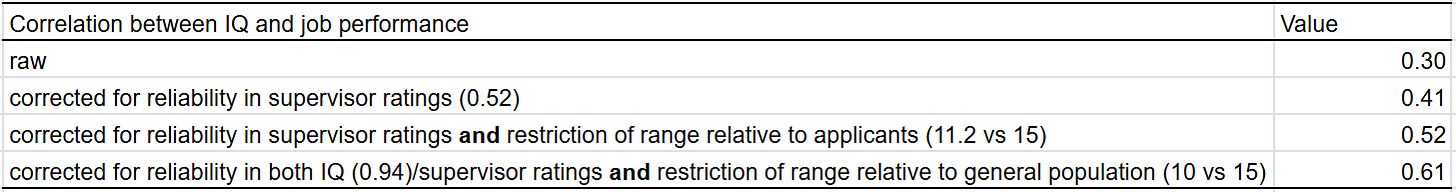

The best meta-analysis on the relationship between IQ and job performance, conducted by Hunter & Hunter, finds a mean correlation of 0.53. This means that 25% of the variation in job performance can be explained by IQ scores.

This value has been debated in the literature for mainly two reasons3:

The value is adjusted for supervisor ratings.

They assumed that job applicants and the general US population had the same variance in intelligence4.

Controlling for unreliability in supervisor ratings is sensible, as supervisors evaluate employees in different ways and lack omniscience. In fact, the original Hunter & Hunter meta-analysis underestimated the degree to which supervisor ratings are unreliable — they assumed a reliability of 0.6, when in reality it’s closer to 0.52.

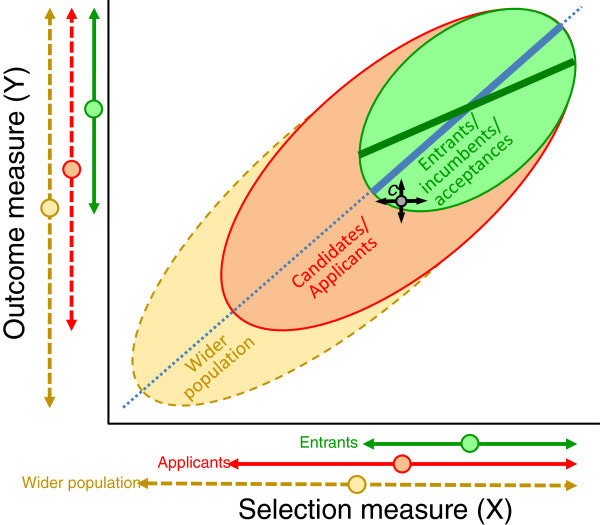

Regarding restriction of range — the idea is that if you calculate a correlation within a sample that is restricted, the relationship will be attenuated in strength:

Critics argued that because job applicants already show reduced IQ variance, correcting for this may exaggerate the incremental value of cognitive tests over existing hiring filters. This is valid as a contextual point, but it does not undermine the interpretation of the corrected validity itself.

The other issue is that H&H assumed that job applicants and the American workforce population were equal5 in terms of variance in intelligence when they corrected for restriction of range. While this asumption sounds ludicrous, it doesn’t turn out to be that big of a problem. Empirically, applicant pools for specific jobs vary only slightly less than the broader applicant pool:

Sackett, P. R., & Ostgaard, D. J. (1994). Job-specific applicant pools and national norms for cognitive ability tests: Implications for range restriction corrections in validation research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(5), 680–684. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.5.680

Correcting validity coefficients for range restriction requires the applicant pool predictor standard deviation (SD). As this is frequently unknown, some researchers use national norm SDs as estimates of the applicant pool SD. To test the proposition that job-specific applicant pools are markedly more homogeneous than broad samples of applicants for many jobs, job-specific applicant pool SDs on the Wonderlic Personnel Test for 80 jobs were compared with a large multijob applicant sample. For jobs at other than the lowest level of complexity, job-specific applicant pool SDs average 10% lower than the broad norm group SDs. Ninety percent of the job-specific applicant pool SDs lie within 20% of the norm group SD, suggesting that reducing a norm group SD by 20% provides a conservative estimate of the applicant pool SD for use in range restriction corrections for other than lowcomplexity jobs.

Given that H&H underestimated the error in supervisor ratings, and overestimated the degree of restriction of range, I calculated a correlation that adjusted for both of these biases6, which turned out to be… 0.52. Turns out the biases cancel out, as they go in different directions. For the sake of transparency, I also posted what each correction does to the effect size:

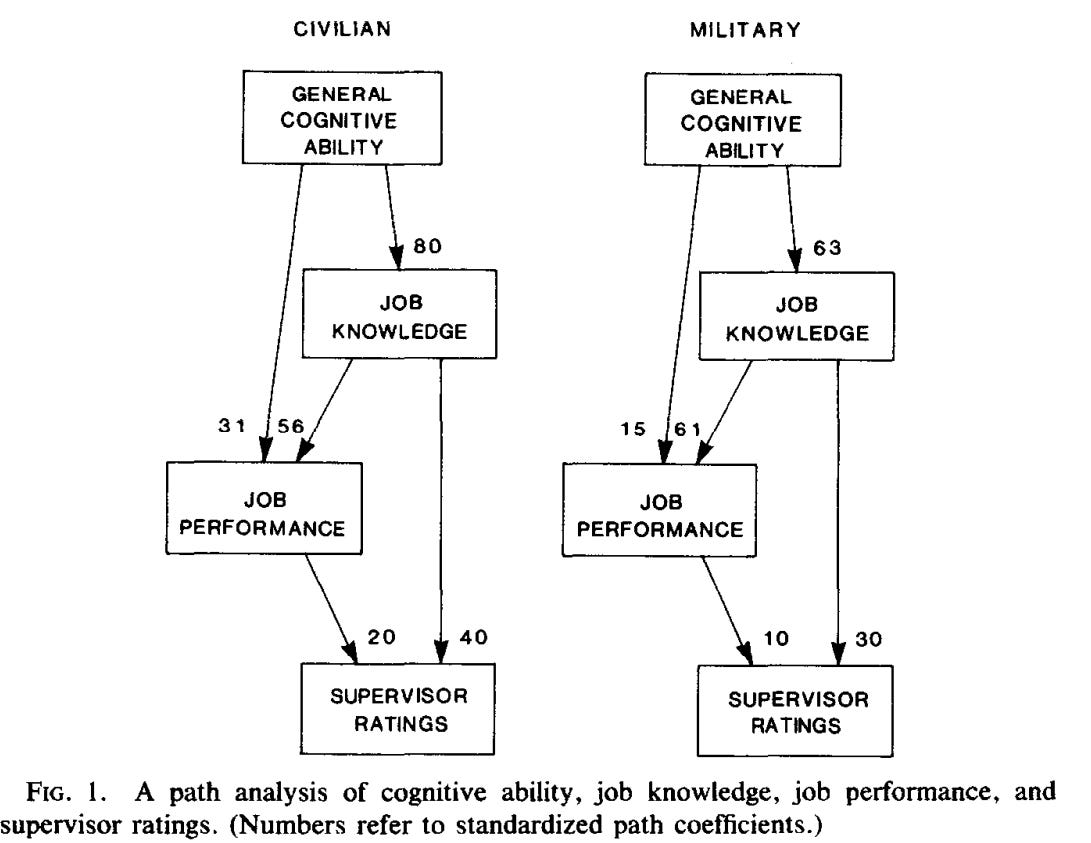

Hunter & Hunter use supervisor ratings as a proxy for productivity. Presumably, there is some bias that results from this, independent of the statistical error that comes from supervisors giving inaccurate ratings. In a followup paper, Hunter did a path analysis where the effect of cognitive ability on job performance was estimated using work sample tests instead of supervisor ratings; the overall effect was more or less the same (0.54 according to this chart):

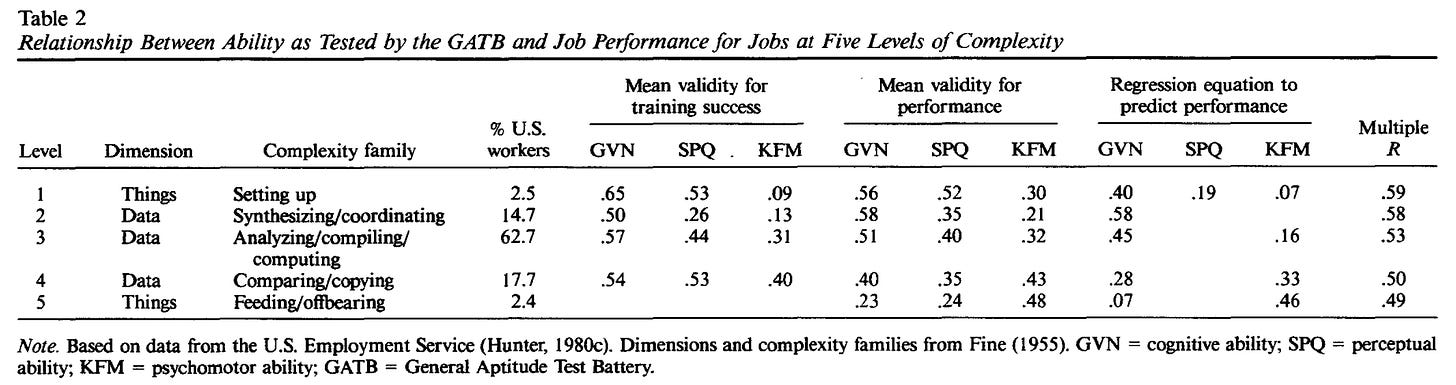

The effect of IQ on performance also varies by occupation, where the most complex jobs have the strongest associations (r = ~0.6), while less complex ones have weaker ones (r = ~0.4). In manual labour jobs, psychomotor ability and dexterity are better predictors of performance than cognitive ability.

IQ vs other selection methods

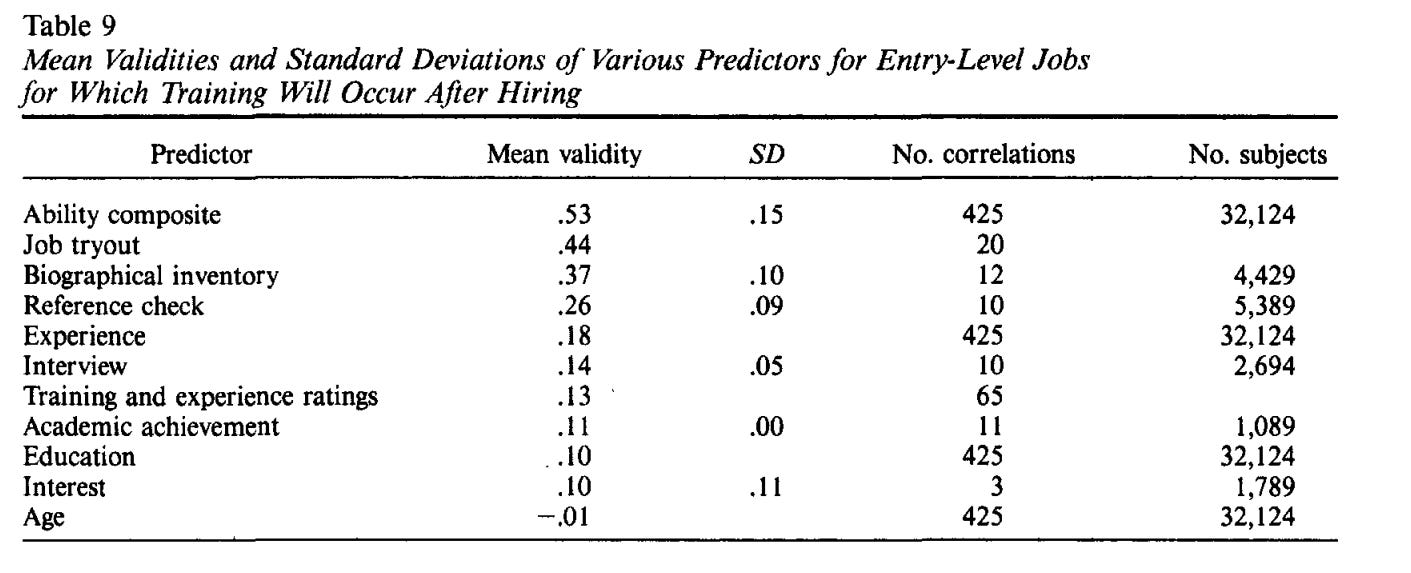

The correlation between job performance and IQ might only be modest, but it should be noted that cognitive ability beats every alternative predictor of job performance except for work samples (r = 0.54).

In most of these cases, it’s not possible to correct for restriction of range, as the distribution of these variables within the reference population is not known. To make the apples to apples comparison, H&H note that the validity of interviews and experience would still be far below that of cognitive ability, even if their validity was corrected for restriction of range.

The key finding for the interview is a mean validity of .14 (in predicting supervisor ratings of performance, corrected for error of measurement). If the restriction in range is as high as that for cognitive ability, then the true mean validity of the interview is .21.

The observed average correlation for ratings of training and experience is .13. If the extent of restriction in range matches that for cognitive ability, then the correct correlation would be .19.

No correction for restriction in range was needed for biographical inventories because it was always clear from context whether the study was reporting tryout or follow-up validity, and follow-up correlations were not used in the meta-analyses.

How effective is test-based selection?

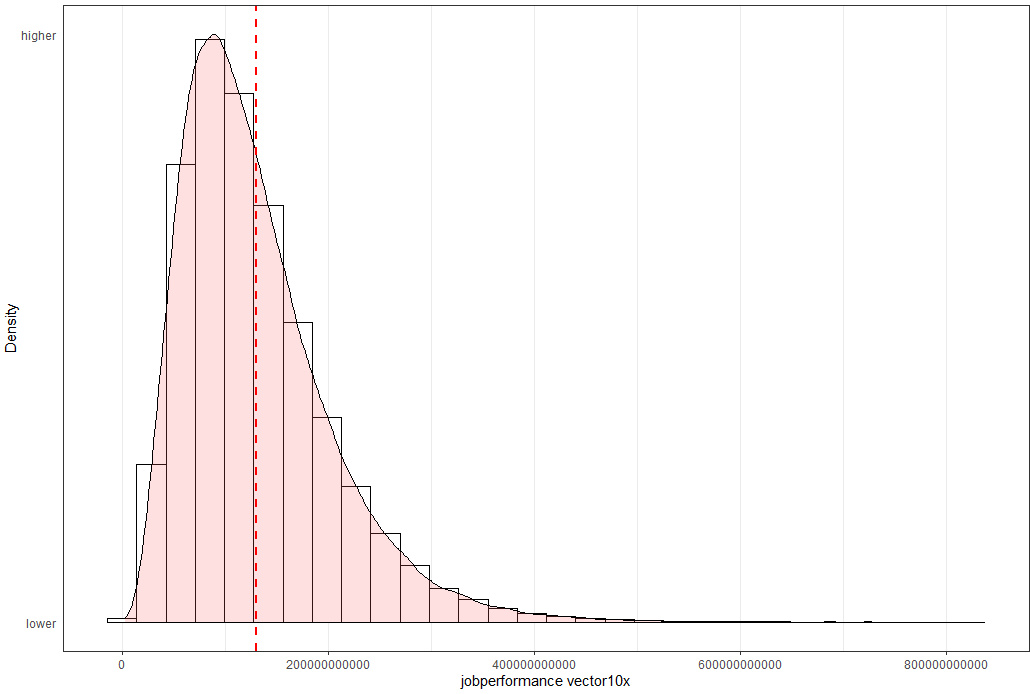

I’m not a fan of the academic literature on productivity, particularly the 10x literature which argues that there are massive differences between the best and worst employees. It is often unclear whether these “10x” estimates refer to the actual difference between the most and least productive workers in a sample, or merely the ratio between the tails (e.g., top 1% vs. bottom 1%). If it’s the former, then the difference will be imprecisely estimated because of sample size variance.

It’s also not clear what constitutes an objective measurement of job performance. Some software engineers might write more lines of code but at a lower quality. This also applies to art; popular films aren’t necessarily good ones.

That said, the idea that the difference between the best and worst employees in complex occupations is an order of magnitude (10x) seems intuitive to me. So much, that I won’t bother trying to justify it with academic literature.

I will be assuming from the get-go that the difference in productivity between the top 1% and bottom 1% within software engineers (just an example) is anywhere from 5x to 25x. I will be using the correlation between job performance and IQ that is adjusted for the reliability of supervisor ratings and restriction in range relative to job applicants. Presumably, the correlation between IQ and job performance could vary anywhere from 0.4 to 0.6 due to the typical heterogeneity and error that occurs in meta-analyses, so said uncertainty will be integrated into the model as well.

I chose a right-tailed gaussian distribution for productivity:

The base case is that the employees are just typical software engineers (SWE). According to Wolfram’s 2023 paper, the average IQ of a software developer is 111. Based on a table in this paper, the standard deviation of IQ within complex professions at the ~111 IQ level is about 12SD, so I will use that as an estimate for the variance in IQ within SWEs. Given that so many people apply for SWE jobs, I think it is plausible that a firm could set a minimum requirement of an IQ of 115 to become a SWE. Without sacrificing for other targets they use for job performance, that is.

Under these parameters, I estimated the percentage improvement in productivity that would result from selecting only SWEs with IQs above 1157, in comparison to normal hiring methods (which lead to SWEs with average IQs of 111). Based on the simulation, selecting for SWEs with IQs above 115 would result in an increase in productivity of 10-30%8.

Which might not sound that large, but for a company as large as Telsa, that would translate to a gain of $1-3 billion in terms of net income every year. Given the smarter employees would be slightly more expensive, and that most occupations lower variance in terms of productivity, I’d wager that the real gain could be anywhere from $100M to $1B per year.

The math at the aggregate level is also supportive of the idea that selection for IQ works. The correlation between IQ and job performance (r = 0.52) is higher than the correlation between the correlation between IQ and income (r = 0.35), especially when you consider that the correlation between IQ and income will be weaker within people who share the same job. There is also more variance in productivity than income, so even if the correlations were the same, IQ selection would still be efficient.

It’s not really possible to estimate the productivity gain if every firm selected employees based on IQ, as talent allocation is zero sum. Presumably, the filtering would result in the higher IQ workers being fed into occupations with larger variance in productivity, which would yield a net economic benefit, though I am not sure how large said benefit would be in practice.

All of these statistics assume that the test involved is a highly reliable test like the GATB or WAIS; in practice a lot of firms that engage in employment testing often have tests that are too short or incomplete, which will diminish the efficacy of testing. Matrix reasoning tests, for example, only correlate with full scale IQ at 0.7. There’s a tradeoff between test length and reliability here; the best tests will be as short as possible and as reliable as possible. For this purpose, I recommend crystalised ability measures like general knowledge, mathematics, and verbal ability.

In real terms

On an emergent level, employees primarily possess four qualities:

Cognitive talent: ability to extract information from information, solve problems, and make intuitive judgements. Some talent is also task-specific — some people are good writers but awful mathematicians. IQ will measure most cognitive talent, but not all of it.

Energy: ambition, passion, physiological health, and activity. It doesn’t come from personality or even incentives, but a kind of irrational drive that comes from the pursuit of mastering the thing in itself.

Character: egolessness, emotional stability, work ethic, and sensitivity to the thoughts and feelings of others. This is analogous to the psychological concept of stability, where there are strong positive intercorrelations between emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

Polish: appearance, charisma, and ability/willingness to manipulate situations and perceptions to their advantage. People with polish can pretend to have good character and to a lesser extent talent/energy.

In my opinion, talent > energy > character > polish in terms of productivity, though this varies substantially by occupation. Polish is essential for professions centered around persuasion or performance (e.g., acting), but far less for technical ones (e.g., academics).

I think a lot of the appeal of IQ testing online comes from the fact that it selects people based on their talents and not polish. The problem is that said selection ignores character and energy, leading to the hiring of potentially egoistic or lazy employees who could be hiding their shortcomings with a layer of polish.

One could argue that, in a corporate environment, those kinds of things shouldn’t matter. But evidently they do. In fact, the kind of people who disregard the feelings or thoughts of others when acting or speaking would recoil at the idea of being treated the same by their peers. Tactlessness usually reflects a lack of character and self-awareness, not polish.

References can’t unveil this coat of polish because the incentives for employers to give other employers accurate references don’t exist. If anything, they are perverse: employers might readily recommend employees with poor character or talent to get them off their plate. It’s an unfixable problem; personality tests are too unreliable and easy too game. Ideally workers would be vetted for IQ first, and then when they have the opportunity to work at the firm, they are promoted based on their productivity; this would still gate untalented but potentially productive employees from the system.

Why don’t firms use IQ testing?

People often ask why intelligence testing isn’t popular in firms if it’s supposedly so effective; there is no one answer to this question. It’s often raised in the lens of the “free market”, that perhaps the fact that IQ testing is unpopular demonstrates that it doesn’t work.

There are some occupations where it simply doesn’t make sense — jobs with low demand, low variance in productivity between workers (e.g. assemblyline workers), and where skill is highly legible (e.g. artists, musicians) do not benefit from cognitive testing. Because hiring methods are mimetic, it’s inevitable that managers who would benefit from selecting from IQ might copy the hiring methods of other managers who do not need to do so.

“IQ” is a socially controversial concept, some people believe in it, others don’t, so it’s inevitable that some businesses will not use it even if they are incentivised to.

Beyond being controverisal, IQ tests are also gauche; stigmatised on grounds of being racist, classist, ageist, and nerdy. They assign people a single number that is assumed to measure intelligence, something that is considered to be innate and also valuable, a dynamic which creates resentment and anxiety.

Some people don’t like it when status-associated traits are explicitly measured out in the open. Some of this is just egalitarian drives, but it also has to do with preferences for implicit or ambiguous hierarchies which allow people to preserve their egos.

Interviews, references, and holistic impressions might be less effective at scale, but they also give evaluators a pretense of agency or mastery when selecting employees. IQ tests are cold and lazy.

The effect of selecting employees for IQ presumably varies by company. I doubt Microsoft, for example, would see large gains from test score selection, as most of their value comes from a product that they’ve already built; though I would assume that if Microsoft was more intelligent they would make decisions that result in them maintaining their market share for a longer period of time. Startups would probably see the greatest success from filtering hires based on intelligence, as their value comes from products they need to create in the future.

Disparate impact

By demographic group: men and women have roughly the same IQ scores, and the elderly perform worse than the young, though much better than people would expect. Some ethnic minorities such as blacks and hispanics perform worse on IQ tests in comparison to whites.

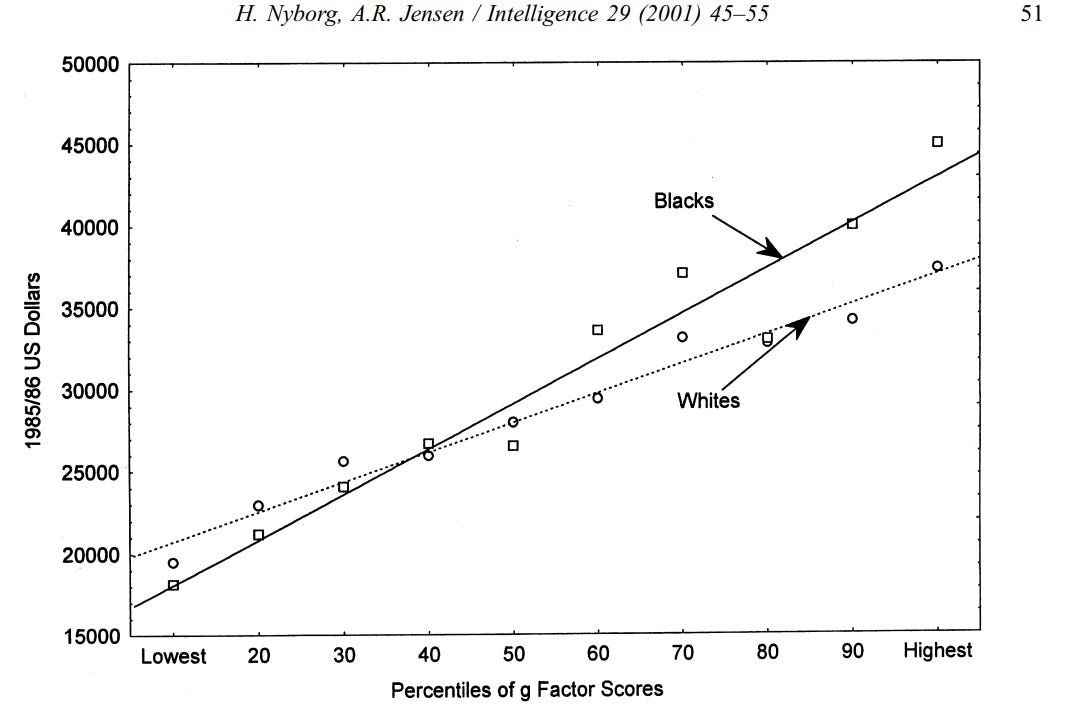

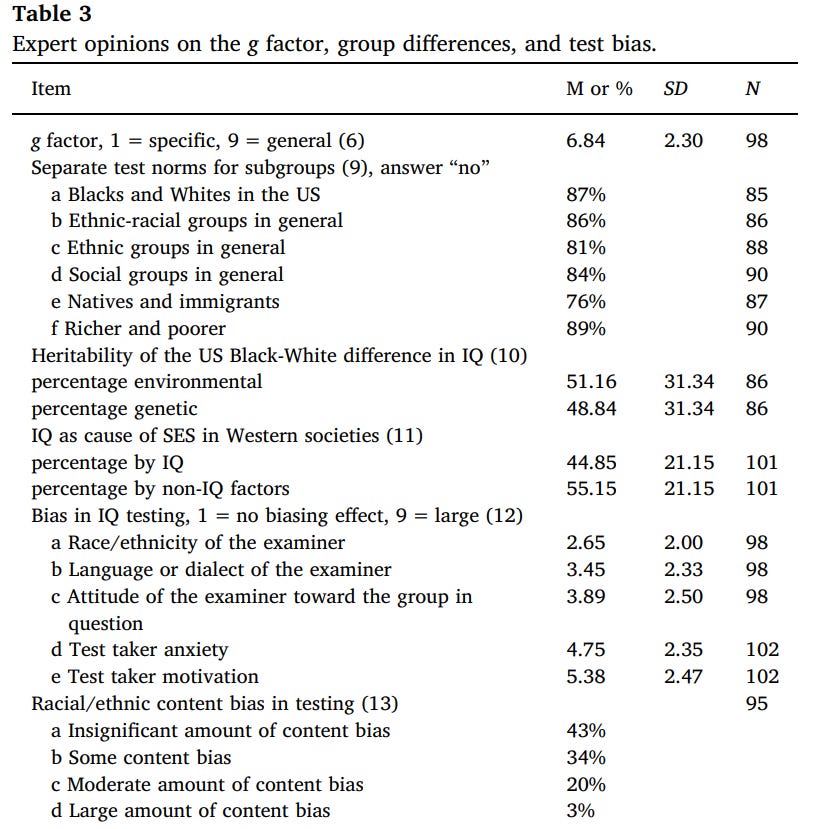

Independent of the causes of these associations, IQ tests typically show little evidence racial or sexual bias at the aggregate level — See Jensen 1980 for an extended review of this topic. In summary, bias in intelligence testing is assessed by regressing an outcome variable of interest (e.g. training success, income) onto IQ within two groups. Bias can be assessed in terms of intercept and slope: if one group has consistently better performance in comparison to what is expected based on their IQ, then the test is likely biased against them9.

Example of a specific test of this hypothesis (though not an explicit one):

I should also mention that it’s the majority opinion within intelligence research that IQ tests are not racially biased10.

So

If you feel like you need to select your employees on the basis of IQ, you probably do. The since the goals and situations of employers will differ. If the occupation is one where work samples or job knowledge tests are easy to administer, reliable, and effective, I would advise for using those regardless of situation; otherwise, IQ tests should do just fine.

Yes:

In the 1950s, Duke Power‘s Dan River Steam Station in North Carolina had a policy restricting black employees to its “Labor” department, where the highest-paying position paid less than the lowest-paying position in the four other departments. In 1955, the company added the requirement of a high school diploma for employment in any department other than Labor, and offered to pay two-thirds of the high-school training tuition for employees without a diploma.[3]

On July 2, 1965, the day the Civil Rights Act of 1964 took effect, Duke Power added two employment tests, which would allow employees without high-school diplomas to transfer to higher-paying departments. The Bennett Mechanical Comprehension Test was a test of mechanical aptitude, and the Wonderlic Cognitive Ability Test was an IQ test measuring general intelligence.

Which should be easy to do now, given all of the literature that supports the effect of intelligence on productivity.

Other criticisms:

Opaque causality: true, but selection concerns predictive validity, not causality.

Validity of IQ is decreasing in recent years according to meta-analysis: doubtful, but possible. These kind of time trend statistics are easy to p-hack by introducing different studies or moderators. I also don’t see any obvious logical explanation for why the value of IQ would be decreasing.

Publication bias: inevitably an issue with any pool of literature, though the largest studies (first is .39, second is .65) I found on IQ and job performance don’t disagree with the meta-analytic mean.

Ethics: selection is imperfect and luck is a thing. Nevertheless, the more accurate and efficient selection is, the more fair it is by definition.

Alternatively. More on the subject:

This is actually something I initially misunderstood.

See page 166:

If the test standard deviation is smaller in the study sample than in the applicant pool, then the validity coefficient for workers will be reduced due to range restriction and will be an underestimate of the true validity of the test for applicants. If the standard deviation for the applicant pool is known, the ratio of study SD to applicant SD is a measure of the degree of range restriction, and the validity coefficient can be corrected to produce the value that would result if the full applicant population had been represented in the study. In the GATB data base the restricted SD is known for each test; however, no values for the applicant pool SD are available. Hunter dealt with this by making two assumptions: (1) for each job, the applicant pool is the entire U.S. work force and (2) the pooled data from all the studies in the GATB data base can be taken as a representation of the U.S. work force. Thus Hunter computed the GVN, SPQ, and KFM SDs across all 515 jobs that he studied. Then, for each sample, he compared the sample SD with this population SD as the basis for his rangerestriction correction. The notion that the entire work force can be viewed as the applicant pool for each job is troubling. Intuitively we tend to think that people gravitate to jobs for which they are potentially suited: highly educated people tend not to apply for minimum-wage jobs, and young high school graduates tend not to apply for middle-management positions. And indeed there is a large and varied economic literature on educational screening, self- selection, and market-induced sorting of individuals that speaks

R code:

#going through every possibility from 0 to 0.53

possible_range <- seq(from=0, to=0.53, by=0.005)

error <- rep(0, length(possible_range))

iteration_product <- data.frame(i_rxy = possible_range, error_term = error)

sd_ratio = 0.67

assumed_unrestricted_sd = 15

assumed_restricted_sd = assumed_unrestricted_sd*sd_ratio

corrected_rxy = 0.53

#R = (rS/s)/ sqrt(1-r^2 + r^2(S^2/s^2)).

#r = R * sqrt(1-r^2 + r^2(S^2/s^2)) * s/S

for(i in 1:length(possible_range)) {

inferred_rxy_value = iteration_product$i_rxy[i]

#rearranged correction formula

inferred_rxy_formula <- corrected_rxy * sqrt(1-inferred_rxy_value^2 + inferred_rxy_value^2*(assumed_unrestricted_sd^2/assumed_restricted_sd^2)) * assumed_restricted_sd/assumed_unrestricted_sd

iteration_product$error_term[i] <- (inferred_rxy_formula-inferred_rxy_value)^2

}

iteration_product

#minimised at 0.385

uncorrected_r <- iteration_product$i_rxy[iteration_product$error_term==min(iteration_product$error_term)]

#going from 0.6 to 0.52 supervisor rating rxx

corrected_for_supervisor <- uncorrected_r*sqrt(0.6)/sqrt(0.53)

corrected_for_supervisor

#10% lower than 15 = 13.5

assumed_unrestricted_sd_true = 13.5

assumed_restricted_sd_true = assumed_restricted_sd

true_ratio <- assumed_restricted_sd_true/assumed_unrestricted_sd_true

true_corrected_rxy <- psych::rangeCorrection(r = corrected_for_supervisor, sdu = assumed_unrestricted_sd_true, sdr = assumed_restricted_sd_true, case=2)

true_corrected_rxyDemonstration:

> IQ_vector = rnorm(100000, mean=100, sd=15)

> jobperformance_vector <- IQ_vector*0.53 + rnorm(100000, mean=100, sd=15)*sqrt(1-0.53^2)

>

> sd(jobperformance_vector)

[1] 15.028

>

> empirical <- data.frame(IQ = IQ_vector, job_performance = jobperformance_vector)

>

> pro100 <- empirical %>% filter(IQ > 100)

> rxy <- cor(pro100$IQ, pro100$job_performance)

> sr <- sd(pro100$IQ)

> su <- sd(empirical$IQ)

>

> psych::rangeCorrection(r=rxy, sdu=su, sdr=sr, case=2)

[1] 0.53679

> cor(empirical$IQ, empirical$job_performance)

[1] 0.53296

> R = (rxy * su/sr)/ sqrt(1-rxy^2 + rxy^2*(su^2/sr^2))

> R

[1] 0.53679These SWEs have an average IQ of 122.

R code:

generate_perf <- function(pe, ere) {

raw_perf <- IQ_vector*ere + rnorm(100000, mean = 100, sd = 15) * sqrt(1 - ere^2)

raw_perf^pe

}

ratio_error <- function(p, target_ratio, er) {

perf <- generate_perf(p, er)

q <- quantile(perf, probs = c(0.01, 0.99))

ratio <- q[2] / q[1]

(ratio - target_ratio)^2

}

# Solve for exponent p

solve_exponent <- function(target_ratio, r) {

optimize(ratio_error, interval = c(0.1, 20), target_ratio = target_ratio, er = r)$minimum

}

p5 <- solve_exponent(5, 0.5)

p10 <- solve_exponent(10, 0.5)

p15 <- solve_exponent(15, 0.5)

p20 <- solve_exponent(20, 0.5)

p25 <- solve_exponent(25, 0.5)

p5

p10

p15

p20

p25

jobperformance_vector <- (IQ_vector*0.5 + rnorm(100000, mean=100, sd=15)*sqrt(1-0.5^2))^p15

q <- quantile(jobperformance_vector, probs = c(0.01, 0.99))

q

###############################

set.seed(1)

IQ_vector <- rnorm(100000, mean = 100, sd = 15)

noise_generator <- rnorm(100000, mean = 100, sd = 15)

people <- data.frame(IQ = IQ_vector, noise = noise_generator)

people$selector <- people$IQ + people$noise

r_variance <- seq(from=0.4, to=0.6, by=0.01)

byx_variance <- seq(from=5, to=25, by=1)

daframe <- data.frame(temp = rep(0, length(r_variance)*length(byx_variance)))

daframe$byx <- rep(0, length(r_variance)*length(byx_variance))

daframe$r <- rep(0, length(r_variance)*length(byx_variance))

it <- 1

for(r_value in r_variance) {

for(byx_value in byx_variance) {

p_exp <- solve_exponent(byx_value, r_value)

people$job_performance <- (people$IQ*r_value + rnorm(100000, mean=100, sd=15)*sqrt(1-r_value^2))^p_exp

mean_111 <- people %>% filter(selector>208)

plus_115 <- people %>% filter(IQ>115)

ratio115to111 <- mean(plus_115$job_performance)/mean(mean_111$job_performance)

daframe$r[it] <- r_value

daframe$byx[it] <- byx_value

daframe$ratio[it] <- ratio115to111

it <- it + 1

}

}

daframe

It’s not a certain thing as outcome variables can also be biased, the magnitude of the bias might not be practically significant, and statistical significance can fail, but generally yes that is the appropriate conclusion.

Your analysis of the legality of using IQ tests to hire employees is undercooked.

Two cases of the Supreme Court—Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (which you discussed) and Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody—helped make the use of IQ tests prohibitively expensive. In Albermarle, the Supreme Court applied the relevant EEOC regulations to a company that used the Wonderlic test, the Revised Beta Examination, and the Bennet Mechanical Comprehension Test for hiring:

"The EEOC has issued ‘Guidelines' for employers seeking to determine, through professional validation studies, whether their employment tests are job related. 29 CFR pt. 1607. These Guidelines draw upon and make reference to professional standards of test validation established by the American Psychological Association. The EEOC Guidelines are not administrative regulations promulgated pursuant to formal procedures established by the Congress. But, as this Court has heretofore noted, they do constitute '(t)he administrative interpretation of the Act by the enforcing agency,’ and consequently they are ‘entitled to great deference.’ Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S., at 433-34, 91 S.Ct., at 854. See also Espinoza v. Farah Mfg. Co., 414 U.S. 86, 94, 94 S.Ct. 334, 339, 38 L.Ed.2d 287 (1973). Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 430-31 (1975).

The message of these Guidelines is the same as that of the Griggs case—that discriminatory tests are impermissible unless shown, by professionally acceptable methods, to be ‘predictive of or significantly correlated with important elements of work behavior which comprise or are relevant to the job or jobs for which candidates are being evaluated.’ 29 CFR s 1607.4(c)." [end of Supreme court quote]

The current rules—see 29 CFR section 1607—make using IQ tests for hiring prohibitively expensive, although the regulations allow their use under certain circumstances. Any company that wants to use IQ tests in their hiring process must rigorously test this process and has the burden to prove that the test works. In other words, IQ tests are presumed to cause an “adverse impact” and discriminate in violation of the Civil Rights Act under the current regulations. And if a company fails to meet this burden in court, it could face severe penalties, such as punitive damages. Given that the Court gives “great deference” to these regulations in interpreting the equal employment opportunity provisions of the Civil Rights Act, these regulations are the main hindrance to the adoption of IQ tests in hiring employees.

The military also, basically, hard selects for IQ for any specific role using ASVAB scores:

https://www.mometrix.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/United-States-Military-Jobs-and-which-ASVAB-Scores-Qualify.pdf