Big five and the lexical hypothesis: explained

Models of personality: part 2

Highlights:

The big five is based on the lexical hypothesis, which posits that the structure of personality is hidden in the adjectives we use to describe other people.

The lexical hypothesis has been validated, but poorly tested. The use of varimax obscures the general factor of personality, without its use, the five factors are valence, dynamism, order, emotional attachment, and transcendence.

The MBTI is not an alternative factorisation of the big five.

The big five started with the lexical hypothesis, which posits that, if there are some fundamental axis on which humans vary, that language can reveal it for us. That is to say, humans invent words that they use to describe other people. Some of those words will naturally overlap, and so principal component analysis1 or factor analysis (almost the same thing) can tease out the underlying factors from our word space. HEXACO, the big five, and the big two are all attempts to decode this factor structure, but with different numbers of factors.

We did it. We tested the lexical hypothesis, and we found extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness.

The problem is that there are many ways to conduct factor analysis, depending on how the factors are rotated. Psychologists default to varimax because it is easier to interpret the factors, but the default method is simply to not rotate the factors at all. No rotation is what happens if you just extract the factors as they naturally are, with #1 being the factor that explains the most variance in the underlying data, #2 being the one that explains the second most variance, and so on.

Varimax is what happens when you take that beautiful, simple thing and twist it. Varimax forces orthogonality2 (uncorrelatednes) in factors by maximising the variance of the squared loadings (squared correlations between variables and factors) within each factor. For example, if you have 18 variables, and extract 3 factors from the data, and you have two possible first factors:

0.5, 0.65, 0.25, 0.5, 0.4, 0.5 …

0.9, 0.94, 0, 0, 0.7, 0.3, 0 …

Varimax will prefer3 the second possibility over the first because it has more variance in terms of loadings. So, even if a general factor exists, its influence will be hidden by the data and redistributed to the lower order factors. The regular big five model appears when you use this particular factorisation method, but not the standard “no rotation” method4.

Andrew Cutler talks about this on his blog and in his dissertation, which involves attempting to extract the big five from written text. So, first, let me try to explain this extremely complex paper, which is the bulk of his dissertation. He uses natural language processing (NLP), specifically a model called DeBERTa, which is a transformer-based encoder model — something similar to standard LLM.

They teased out word associations with promopts, usually this one:

“Those close to me say I have a [MASK][MASK] and [TERM] personality.”

This sentence is repeated for every word, and the hidden states with 1024 dimensions for each blank ([MASK]) are extracted. These theoretically can be converted into probability distributions which eventually predict the likelihood that each blank is a given word in the model (of which there are 30,000 different options). Using these predictions of likelihood is unnecessary, and Cutler only uses the 1024-dimensional word vectors here. Those two vectors are then averaged for each term, and are then correlated with each other, so a correlation matrix is produced, which is then subject to principal component analysis.

He used the classic 435 adjective dataset from Saucier and Goldberg (1996), which contains self-rating data from ~900 undergrads regarding the 435 terms, to test the hypothesis. He also conducted some robustness tests with different prompts or sets of adjectives. The set of adjectives didn’t matter, but sometimes the prompt made a difference.

This is the ultimate test of the lexical hypothesis. It was positive.

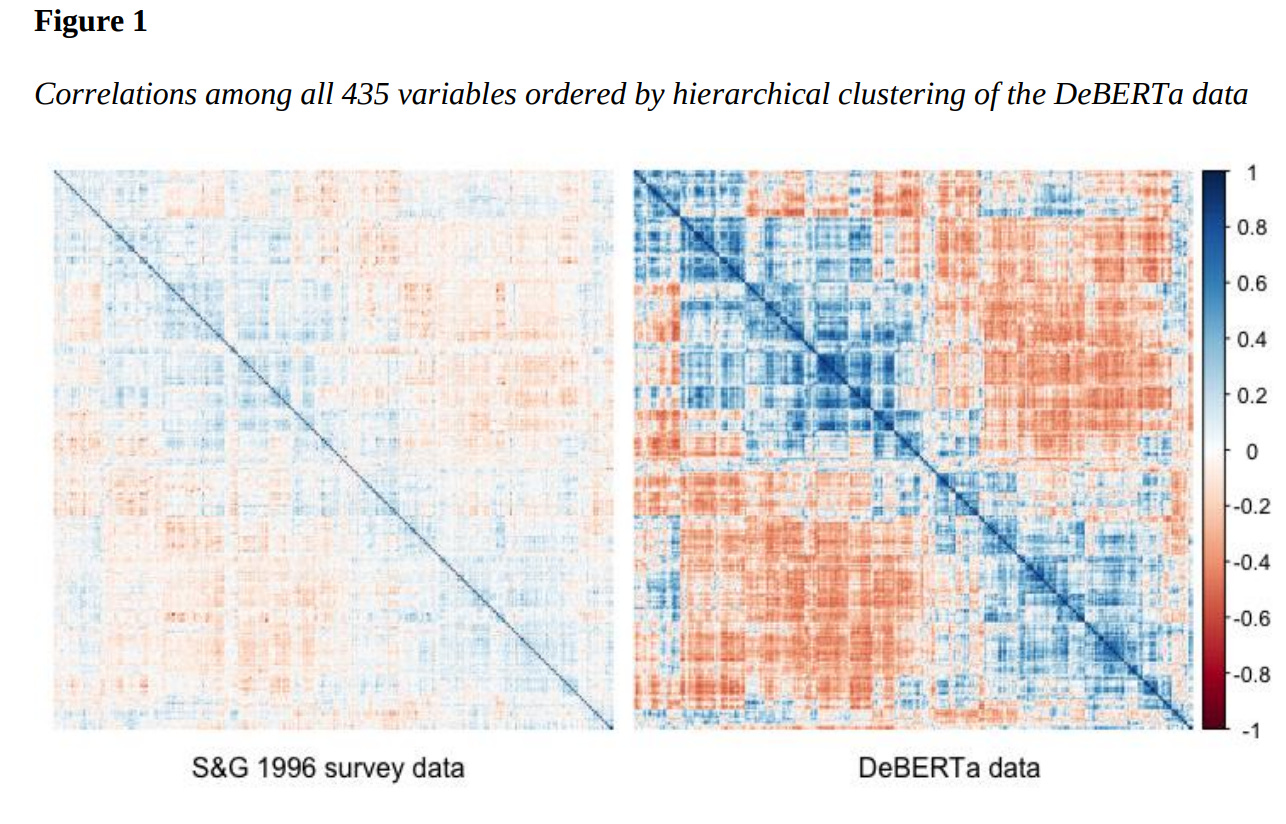

If you map out the correlations between the 435 adjectives in the survey data and the DeBERTa data, the overlap in terms of correlations between words is pretty strong. 75% of the 94,395 correlations between terms were directionally consistent (both were positive or negative) between methods. Besides the similarity in the correlation matrix, the NLP-based method yielded stronger correlations between words than the survey data

In the supplementary materials, he seems to imply that, when the survey and NLP data disagree, the survey data is usually right. Based on what he presents, that seems like a cogent conclusion.

Table 14 also provides a preliminary indication of why the terms are not more perfectly associated, and this is most obvious with the least correlated terms. “Weariless” appears to be well-understood in the S&G data, with nearest and furthest neighbors of “energetic”, “vigorous”, “courageous” and “sluggish”, “lazy”, “lethargic”. The DeBERTa model gets it wrong, with synonyms of “passionless”, “dull”, “lethargic” and antonyms of “intelligent”, “assertive”, “humorous”. This is a bit surprising given the intuitive definition, but some additional research into the frequency of use for this term in ngrams such as “weariless person” suggests that it is rarely used as a personality descriptor; it is not present in Google Books Ngram data since 1900. Despite this poor start for DeBERTa, the circumstances are reversed for the second term (“transparent”) as it has been misunderstood by respondents in the S&G data, on average, but correctly attributed in the DeBERTa data.

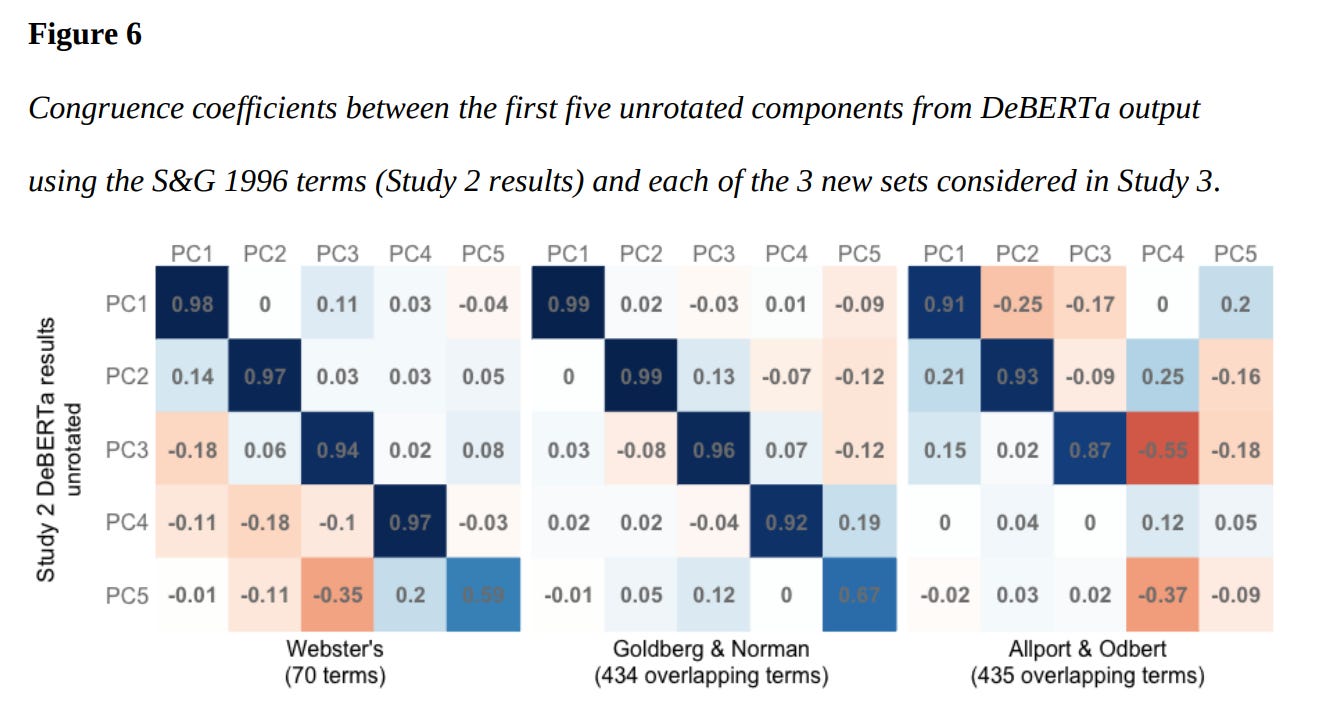

When natural language processing is used but different sets of adjectives are used, the inferred factor structure of personality does differ a bit, but the big three are extracted in all three models.

Now, onto the issue with factor rotations When PCA analysis is conducted on big five data with no factor rotation, you get a slightly different big five:

In the unrotated version, the first factor of personality (PC1) is a negative-signed version of the traditional general factor of personality — having negative loadings on agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness; and a small positive loading on neuroticism.

There is a long-standing debate in the personality psychology field regarding whether a general factor of personality really exists. Some researchers argue the general factor of personality is an artefact of some respondents responding in a more socially desirable way, others think that it reflects a general measure of organic functioning. Personally, I’m not interested in the debate, because the idea that some people are generally “more functional” than others and that this bleeds over in various aspects of their behaviour is just intuitive to me.

In a later post, he labels all of these factors that emerged, but with a different set of adjectives (~2800 from an academic paper) and using a NLP model (ROBERTa). He described them as follows5:

Valence (affiliation)6. The hidden general factor of personality. Loads positively on gentle, nice, easygoing, optimistic, sociable, happy, honest, reliable, sensitive, and loyal; negatively on cruel, mean, moody, selfish, pessimistic, impatient, bossy, and cowardly.

Dynamism. Loads positively on impulsive, adventurous, extraverted, ambitious, aggressive, brave, funny, and emotional; negatively on reserved, conservative, shy, cautious, serious, and calm.

Order. Loads positively on determined, stern, exacting, direct, domineering, stubborn, and persistent; negatively on gullible, lax, lazy, easygoing, and cowardly.

Emotional Attachment. Loads positively on moody, thoughtful, anxious, fearful, emotional, affectionate, spiteful and caring; negatively on independent, superficial, tactless, and frank.

Transcendence. Loads positively on unique, complicated, troubled, star-crossed, handicapped, mystical, heartbroken, and other-worldly; negatively on unphilosophical, fancy-free, pigheaded, boorish, materialistic, self-centered, and glib.

In the MBTI, the case that all types are equal is easy to make, but for the big five, it is simply not. Valence and order are clearly good. Transcendence, emotional attachment, and dynamism are more ambigious or close to value-neutral.

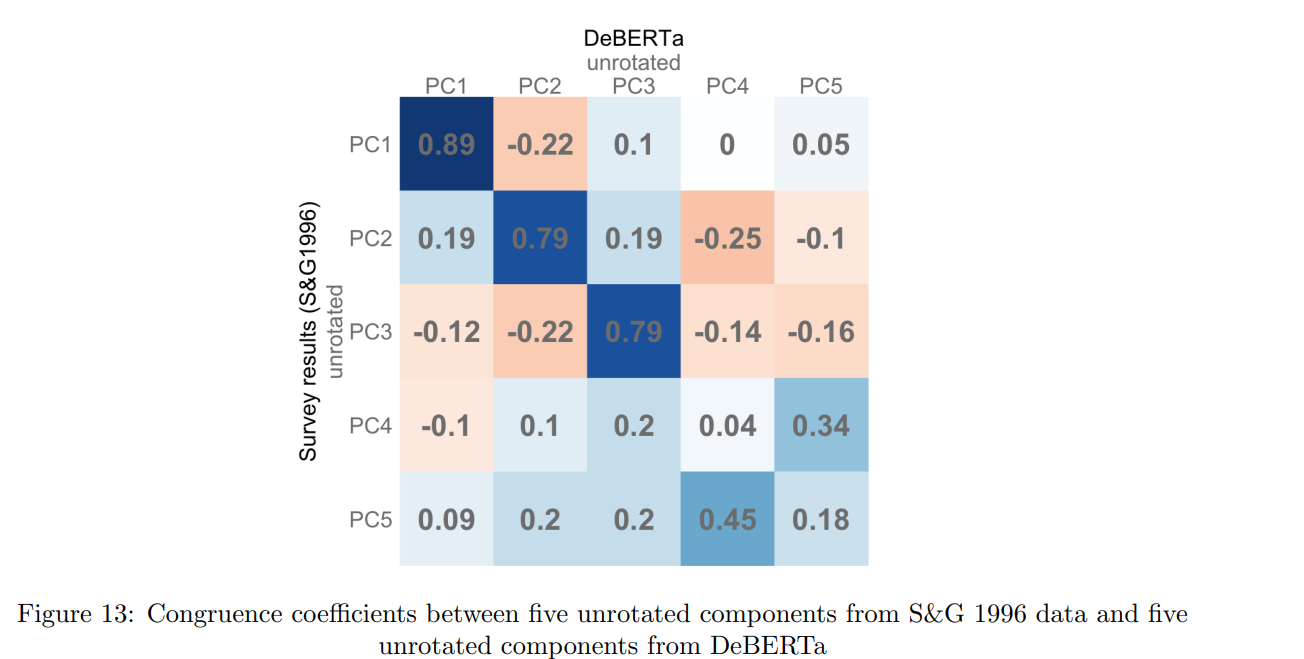

Culter’s dissertation7 shows that the structure of the big five can vary by method (survey data vs DEBERTa aka natural linguistic processing). If you compare the unrotated factors of each of the methods, then only the first three are recovered consistently8. Though it would seem that, generally, the survey data is in the right.

Despite the limitations and inconsistencies of principal component analysis, I think that transcendence and emotional attachment are good candidates for the 4th and 5th factors in the big five. First of all, some people are clearly much more emotionally driven than others if you watch people do things in real life. That’s part of the reason why the big five traditionally has good external validity: it has neuroticism, MBTI does not.

The “transcendence” factor is definitely describing a definitive type of person, and a trait that influences how people act and think. It’s pretty close to MBTI intuiting. Personally the word vector loadings of the transcendence describe me very well, so part of that makes me inclined to think that it is real too.

Beyond my criticisms of how psychologists have treated the lexical hypothesis and created the big five, the lexical hypothesis itself isn’t perfect. I’ll grant that it’s cool, and the fact that it has been empirically supported is extremely cool, but it does have its shortcomings.

The first one is that the test of the lexical hypothesis identifies personality factors according to what is socially considered to be most important. It doesn’t necessarily identify what actually makes people tick and do things. A factor could explain a small amount of variance because there might not be many terms are used to describe it, but it might be salient anyway. It could also explain little variance because people find it difficult to observe in themselves or others. I think it is hard to argue that transcendence and emotional attachment do not have a massive impact on how people feel and behave.

Similarity between the big five and MBTI

The MBTI is a philosophy first, statistics second model; the big five is a statistics first, philosophy second model.

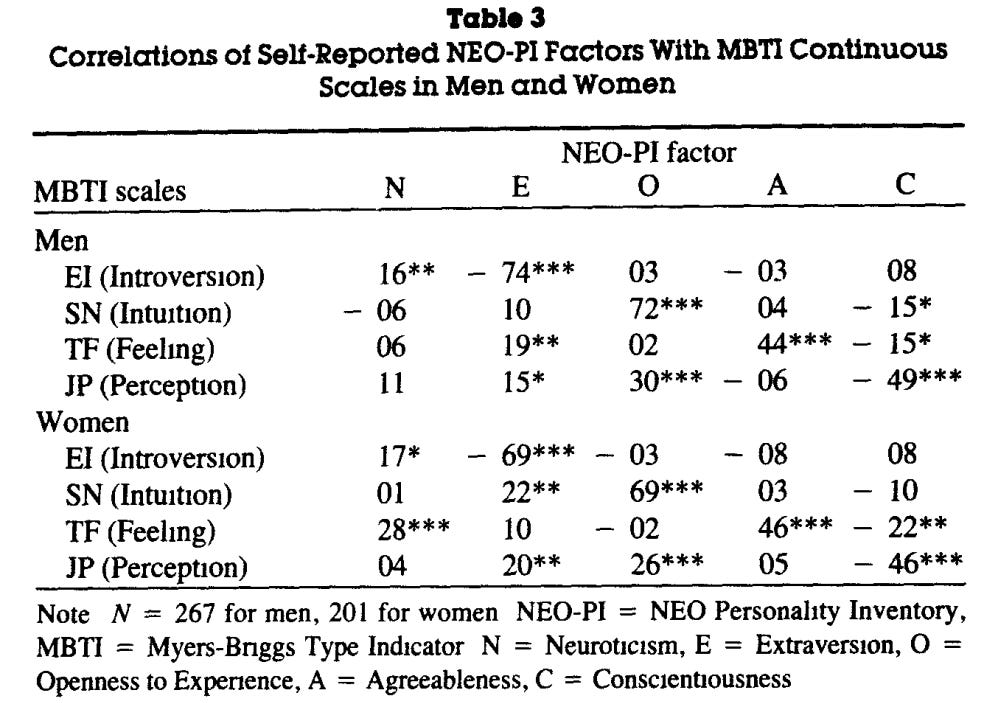

Even if we take the original big five for granted, they don’t even correspond that strongly to the MBTI:

Unsurprisingly, the measures of introversion are highly correlated. Intuiting does strongly correspond with openness, but I suspect this is an artefact of test bias — sensors are more open to physical experiences, and intuitives are more open to abstract concepts.

The correlation between having a feeling>thinking preference and agreeableness is .45. That is not a high correlation. I suspect it exists because most feelings are positive, and if you lean more on your feelings, you end up engaging in more friendly behaviour naturally.

The correlation between judging>perceiving and conscientiousness is also not particularly strong. I suspect it exists because, if you are a conscientious person, then it is easier to administer structure onto the physical world — organise, plan, and schedule things. On the other hand, because the structure and judgement perceivers engage in is internal, their conscientiousness is harder to measure and infer.

I’m not even sure if there is any innate correlation between conscientiousness and judging. I suspect there is, but solely because the average person prefers closure too little and keeping options open too much. As such, conscientious people naturally drift towards more closure than more openness.

Technically, you could try to turn the MBTI into the big five: take the 5 big five traits and make 25 types out of them. The problem is that 25 is way too many to keep track of, and the big five wasn’t really intended to be a typology model, and as a result the types are sloppy and convoluted.

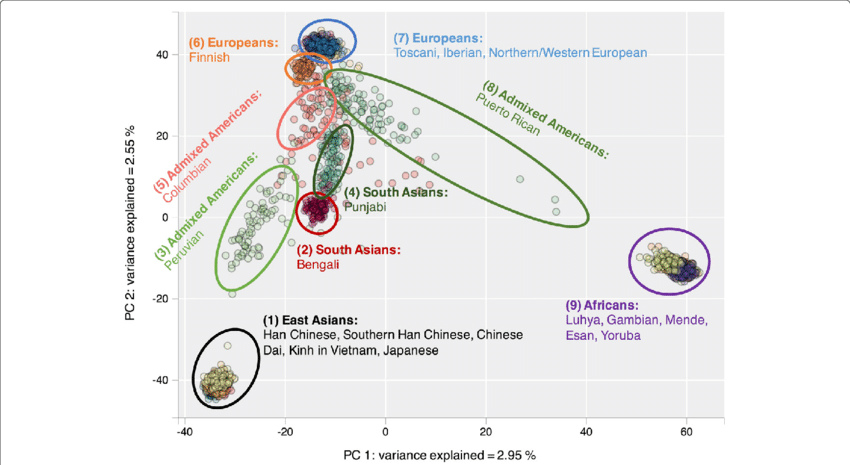

Principal component analysis is a statistical method that involves taking a bunch of data and teasing out a number of factors from it based on how much the variables correlate with each other. Specifically, it extracts a number of abstract, mathematical vectors from a correlation matrix, where the vectors are ordered by the percentage of variance they explain in the underlying data. It’s popular in genetics, where people use correlations between different genetic locations to extract the components that explain the highest amount of variance in the data, which ends up being population structure:

Standard PCA/FA with no rotation also leads to orthogonal factors, but for different reasons.

It doesn’t actually work like this but this is the most intuitive way of explaining it.

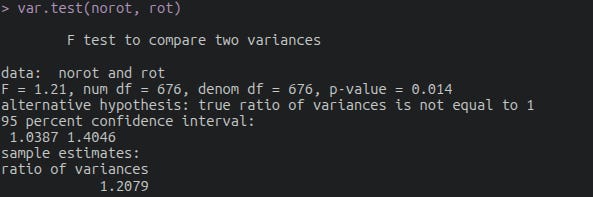

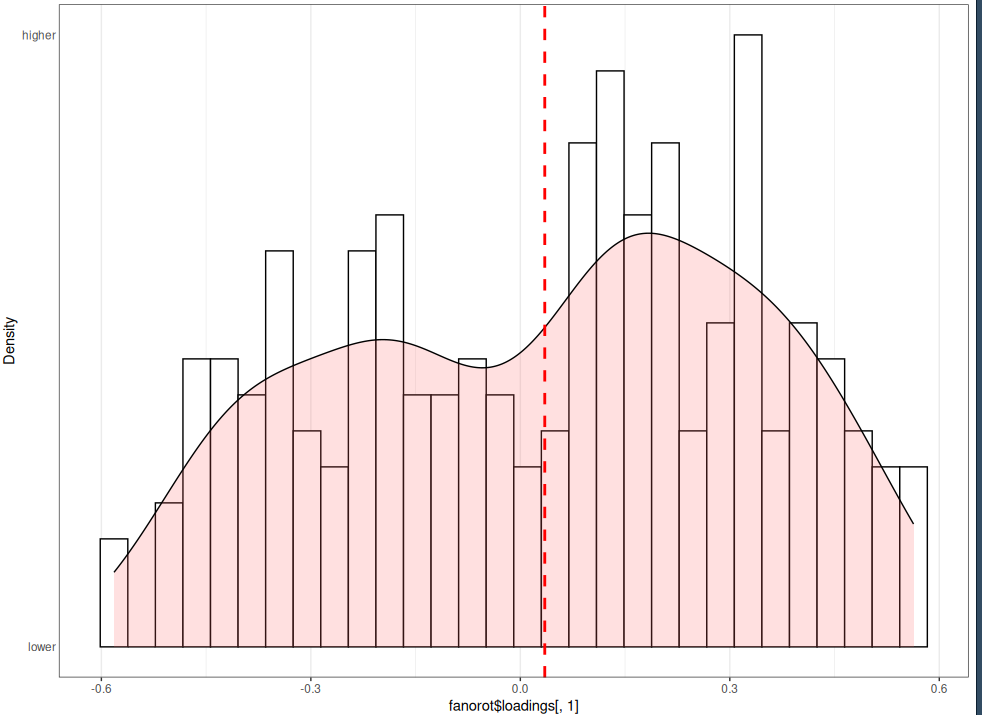

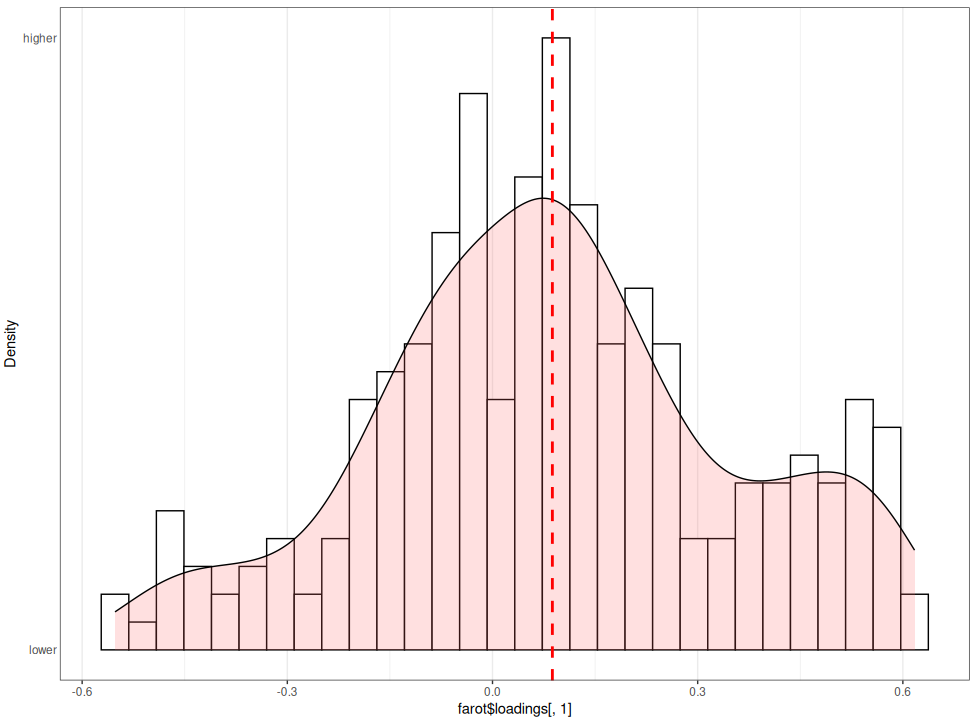

I tested this myself with the 240 item HEXACO dataset on openpsychometrics and the SG 1996 435 adjective dataset — the latter was pre-cleaned by Andrew Cutler. After combining the loadings of both general factors, using no rotation method leads to more variance in loadings, but the p-value was disappointing (p = .01). Sad.

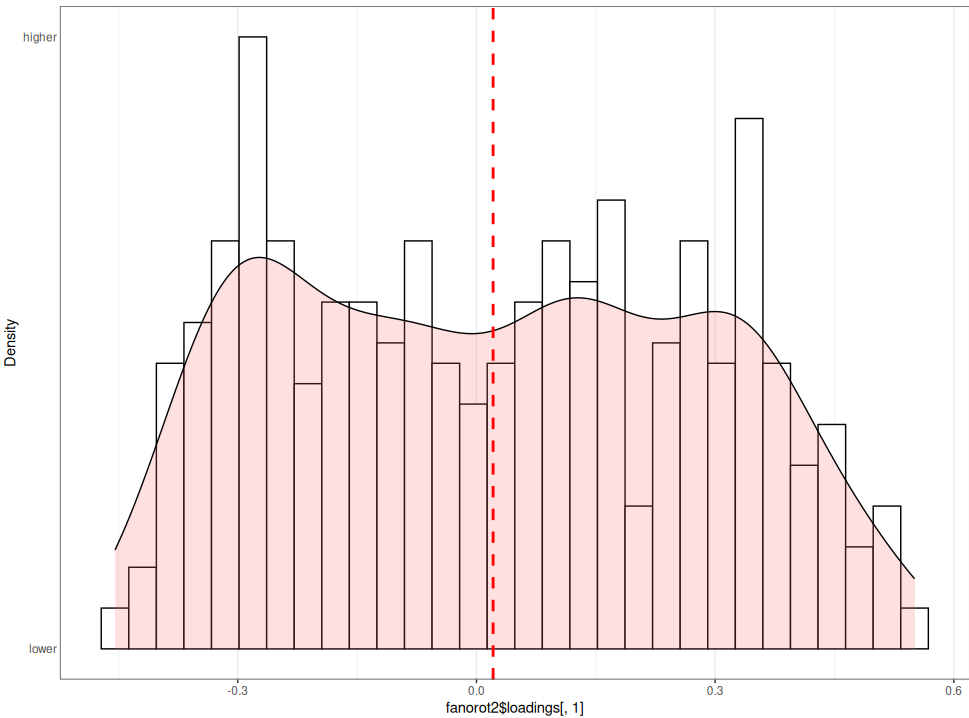

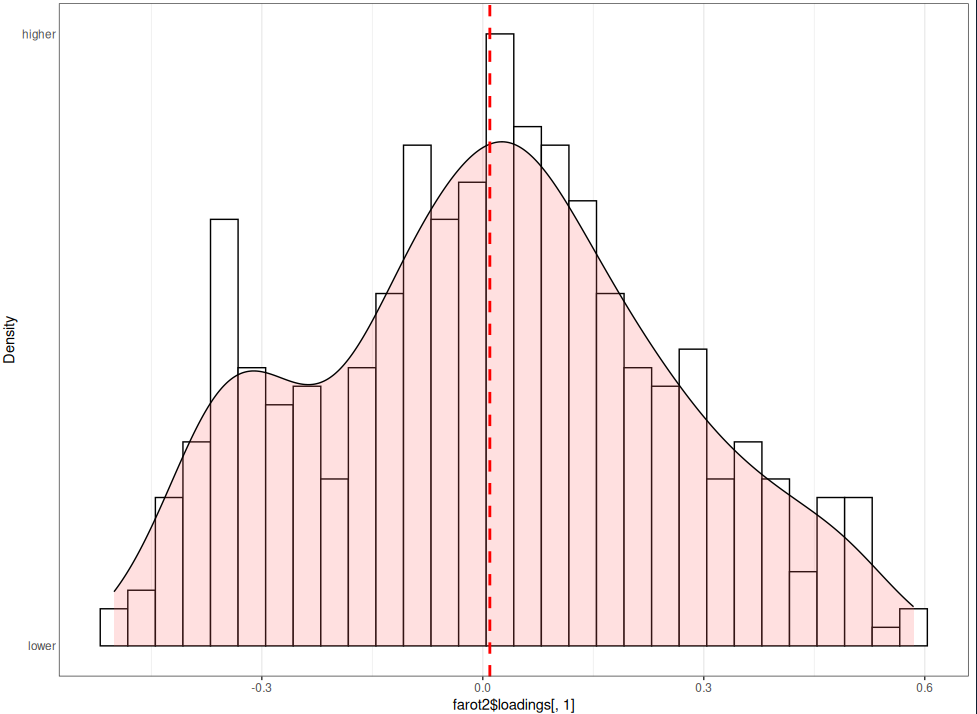

Visually, in both datasets, the varimax (farot) method seems to lead to more concentration of loadings around zero than the no rotation method (fanorot).

HEXACO dataset, no rotation:

HEXACO dataset, varimax:

SG1996 dataset, no rotation:

SG1996 dataset, varimax:

May as well post code, since it is short:

hexaco <- data

psych::fa.parallel(hexaco[, 1:242], nfactors=40)

fanorot <- fa(hexaco[, 1:242], nfactors=5, rotate='none')

farot <- fa(hexaco[, 1:242], nfactors=5, rotate='varimax')

GG_denhist(fanorot$loadings[, 1])

GG_denhist(farot$loadings[, 1])

sd(fanorot$loadings[, 1])

sd(farot$loadings[, 1])

var.test(farot$loadings[, 1], fanorot$loadings[, 1])

##############

sg1995 <- study1SaucierGoldberg1996data

fanorot2 <- fa(sg1995, nfactors=5, rotate='none')

farot2 <- fa(sg1995, nfactors=5, rotate='varimax')

GG_denhist(fanorot2$loadings[, 1])

GG_denhist(farot2$loadings[, 1])

sd(fanorot2$loadings[, 1])

sd(farot2$loadings[, 1])

var.test(fanorot2$loadings[, 1], farot2$loadings[, 1])

##############

norot <- c(fanorot2$loadings[, 1], fanorot$loadings[, 1])

rot <- c(farot2$loadings[, 1], farot$loadings[, 1])

var.test(norot, rot)I added and deleted some words depending on my own discretion and what appeared in other factor analyses (not just that specific model + set of adjectives).

Top 30 loadings for each pole:

considerate, peaceful, respectful, kind, courteous, unaggressive, polite, agreeable, cordial, reasonable, pleasant, benevolent, compassionate, understanding, charitable, helpful, accommodating, cooperative, amiable, tolerant, humble, trustful, patient, genial, altruistic, easygoing, modest, unselfish, friendly, down-to-earth, generous, diplomatic, mannerly, relaxed, selfless, sincere, undemanding, warm, tactful, affectionate

vs

abusive, belligerent, disrespectful, quarrelsome, unkind, rude, bigoted, intolerant, inconsiderate, uncooperative, irritable, vindictive, impolite, prejudiced, antagonistic, ungracious, crabby, egotistical, cruel, surly, uncouth, cranky, scornful, impatient, selfish, egocentric, possessive, greedy, jealous, tactless, combative, callous, conceited, bitter, uncharitable, unsympathetic, unruly, unstable, bullheaded, unfriendly

Andrew Cutler holistically defines it as a tendency to follow the golden rule.

Technically, not sure if this is a publication that was part of the dissertation or the dissertation itself.

Haha nice job! Was not aware of the varimax issue.

I could see why they wanted to go with the big five though; they're simpler to understand. But as you say, yes, some types are better than others.

So: Valence/Affiliation: +C, +A, -N, weak +E; roughly equals the 'stability' or 'alpha' factor. in MBTI, (E)FJ-A.

Dynamism: +E, weak +A, weak +O; roughly the 'plasticity' or 'beta' factor. In MBTI, E(NF).

Order: +C, weak -A, weak +O. In MBTI, (NT)J.

Emotional attachment: +N. In MBTI, this is the -T thing they add on sometimes to add neuroticism back in.

Transcendence: +O. In MBTI, N. There's some weak +E, +A, +N, +C, making this sort of your crystal-gazing INFJ type.

Nitpick: if you made types out of the Big Five you'd have 2^5=32 types. This was actually done by laypeople and called SLOAN, but nobody uses it. The other problem with MBTI is it's dichotomous--usually people are in the middle on some thing, but then you'd have 3^5=243 types; try turning that into a listicle.

The *advantage* of MBTI is, because it's so sunny, people usually know their Myers-Briggs and are often willing to share. I was able to figure out, for instance, all my successful long-term relationships were INs--low extroversion, high openness. I'm lacking the neuroticism info, but you can't have everything.

Such a sad story then.

Big five has many uses and it's very effective. Why not have a more curvy big five indeed?

I suppose it's path dependency