The Politics of Hereditarianism

As time has gone on, “the sphere” on the internet have gone from discussing the science of behavioural genetics to the implications of it. First, there is the issue of whether hereditarianism has policy implications at all, then whether it empirically affects people’s political positions, and finally whether it can function as a political platform. My conclusion is that hereditarianism indeed has massive policy implications, that it does have a moderate effect on people’s political beliefs, but that unfortunately it cannot be a political platform and will stay a fringe position in the near future.

I.

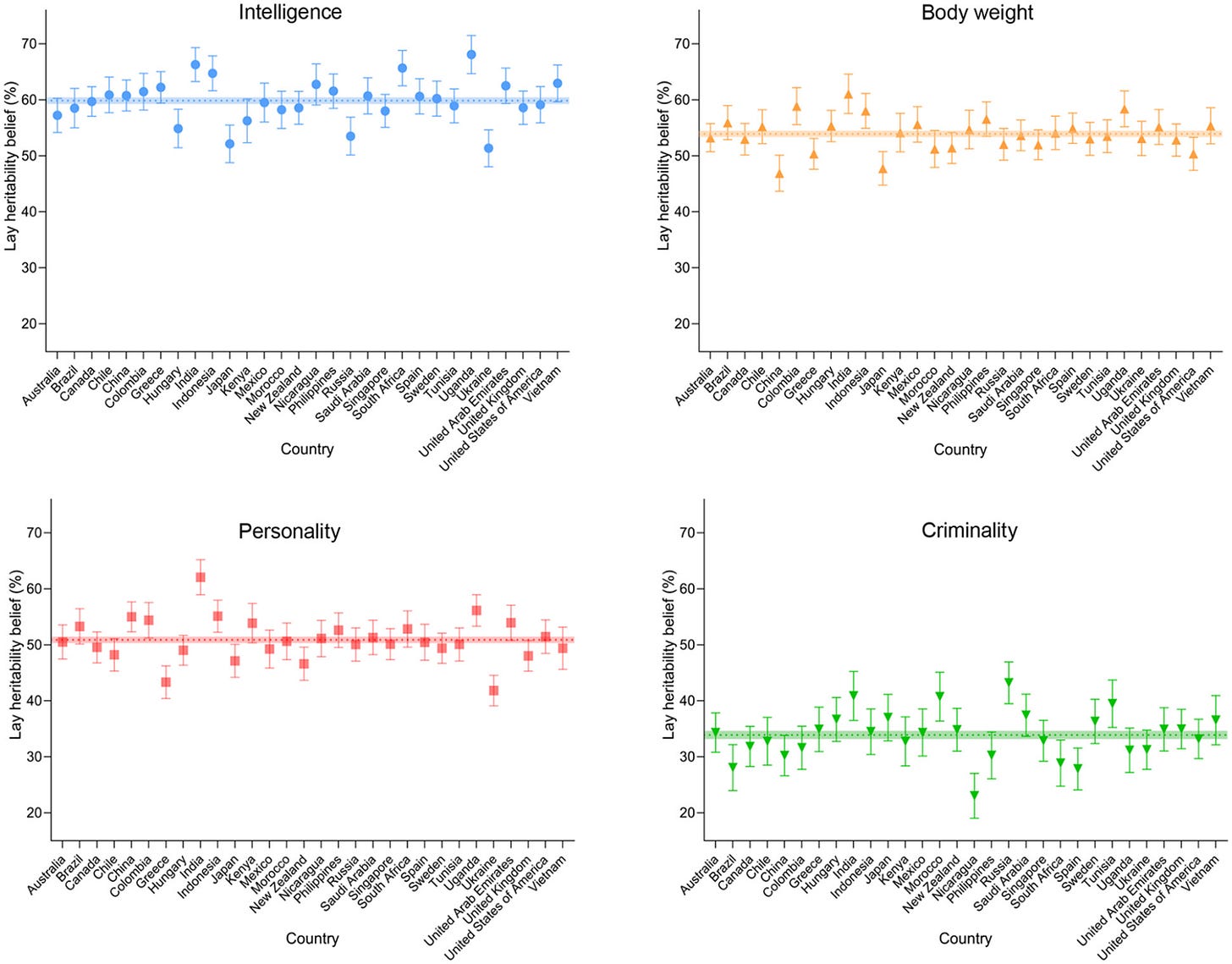

Hereditarianism at the individual level is taken for granted by most of the public: the median human believes that about 50-60% of the variance in intelligence, weight, and personality are caused by genes. I assume would assume these answers vary substantially by person: some people might think that intelligence is 100% innate, while others think that the heritability of intelligence is closer to 15%, like Sasha Gusev.

The estimates made are fairly accurate — for intelligence I’d peg the heritability at 60-90%, personality at 50-90%, criminality at 40-60%, and body weight at 50-80%. The estimated heritability depends a bit on the study and the method: variance in self-reported personality is less heritable (40-50%) than variance in clinical diagnosis or peer-ratings (70-96%). It’s difficult to judge which set of estimates to use — peer ratings or diagnosis might oversample the permanent variance in personality, while self-reports are, well, self-reports.

There is little polling on this, but I would assume that most people think that social interventions are effective, even though it is not what you would predict based on hereditarian theory. The stable component of personality and intelligence are far too heritable to be influenced by interventions. Less heritable traits like income, education, criminality, happiness, and whatnot, beyond being affected by talent, are also affected by a random component that is difficult to predict or measure.

This is not something that is agreed upon among academics — take for example this recent review article on sociogenomics:

Third, heritability is often erroneously interpreted as an index of policy relevance, with higher heritability leaving less room for environmental interventions to have an effect. But as noted by Goldberger (1979, p. 344): “The policy relevant effect of an explanatory variable is properly measured by its regression slope, not by its contribution to R2 ...” His memorable example is that eyeglasses can make a big difference even though naked eyesight is highly heritable. The facts that nutrition has led to large improvements in average height and that variation in height at any point in time is largely explained by genetic factors are not contradictory (Visscher, Hill and Wray, 2008). Moreover, policy can itself change heritability. For example, if income were redistributed from those with a high genetic factor for income to those with a low genetic factor, then the heritability of post-transfer income would be reduced. Rimfeld et al. (2018) find that after Estonia gained independence from the Soviet Union, the heritability of educational attainment and occupational status increased, and they interpret this change as resulting from an increase in meritocracy.

The argument is that the efficacy of interventions is analogous to the magnitude of the regression slope of environmental effects on traits, not the percentage of observed variance that is caused by the environment.

This is fallacious reasoning. There are exceptions to the rule such as eyesight and body weight where a heritability coexists with malleability. But a high heritability implies that, on average, effective interventions are much less likely to be discovered.

Allow me to be more concrete. Heritabilities are affected by the following four factors:

The effect of genes on a trait.

Genetic variance within the population.

The effect of the environment on a trait.

Environmental variance within the population.

The factor that is most relevant in relation to the efficacy of interventions is clearly the third. But the other three matter as well: the larger the first two factors are, the lower the relative impact of an intervention will be. And the lower the environmental variance, the more difficult it is to judge which environmental factors are causal for trait variance. Because of this, heritability and the efficacy of interventions should be expected to strongly correlate.

This is supported by the literature on interventions fairly well, at least the ones that correct for publication bias and other common biases. Allow me to elaborate:

Educational interventions do not increase academic ability.

The effects of IQ interventions fade out after a few years.

Mindfulness interventions are not effective.

Many medical and dietary interventions are probably not effective.

The efficacy of psychotherapy is overstated by publication bias and regression to the mean.

Interventions to reduce criminal reoffending are probably not effective. And Norwegian recidivism is not uniquely low, contra reports from the media.

The cross-sectional relationships between income and crime are not causal, based on studies that use lottery winners to estimate the causal effect.

Relevant to the discourse on interventions is what I like to call the “shared familial confounders” literature, which analyzes whether associations between family background and behaviour survive controls for genetic and cultural confounding.

Take, for example, a study that tracks family income longitudinally and tests whether differences in income within a family predict differences in the criminal offending of children.

We calculated mean disposable family income (net sum of wage earnings, welfare and retirement benefits, etc.) of both biological parents for each offspring and year between 1990 and 2008. Income measures were inflation-adjusted to 1990 values according to the consumer price index provided by Statistics Sweden (http:// www.scb.se/en_/). Econometric researchers have long recognised that single annual income exposure measures generally suffer from substantial measurement error because of their inability to accurately depict long-term SES, often leading to attenuation bias.18,19 Therefore, annual variables were used to calculate the mean parental income throughout each offspring’s childhood (ages 1 through 15).

[…]

To assess the effects also of unobserved genetic and environmental factors, we fitted stratified Cox regression models to cousin (n = 262 267) and sibling (n = 216 424) samples with extended or nuclear family as stratum, respectively. The stratified models allow for the estimation of heterogeneous baseline hazard rates across families and thus capture unobserved familial factors.23 This also implies that exposure comparisons are made within families.24 Model III was fitted to the cousin sample and adjusted for observed confounders and unobserved within extended-family factors. Model IV was fitted on the sibling sample and accounted for unobserved nuclear family factors and for gender, birth year and birth order

They do not.

This is also the case for criminality in the United States, according to the Bell Curve:

We will use both self-reports and whether the interviewee was incarcerated at the time of the interview as measures of criminal behavior. The self-reports are from the NLSY men in 1980, when they were still in their teens or just out of them. It combines reports of misdemeanors, drug offenses, property offenses, and violent offenses. Our definition of criminality here is that the man's description of his own behavior put him in the top decile of frequency of self-reported criminal activity.''0' The other measure is whether the man was ever interviewed while being confined in a correctional facility between 1979 and 1990. When we run our standard analysis for these two different measures, we get the results in the next figure.

Both measures of criminality have weaknesses but different weaknesses. One relies on self-reports but has the virtue of including uncaught criminality; the other relies on the workings of the criminal justice system but has the virtue of identifying people who almost certainly have committed serious offenses. For both measures, after controlling for IQ, the men's socioeconotnic background had little or nothing to do with crime. In the case of the self-report data, higher socioeconomic status was associated with higher reported crime after controlling for 1Q. In the case of incarceration, the role of socioeconomic background was close to nil after controlling for IQ, and statistically insignificant. By either measure of crime, a low 1Q was a significant risk factor.

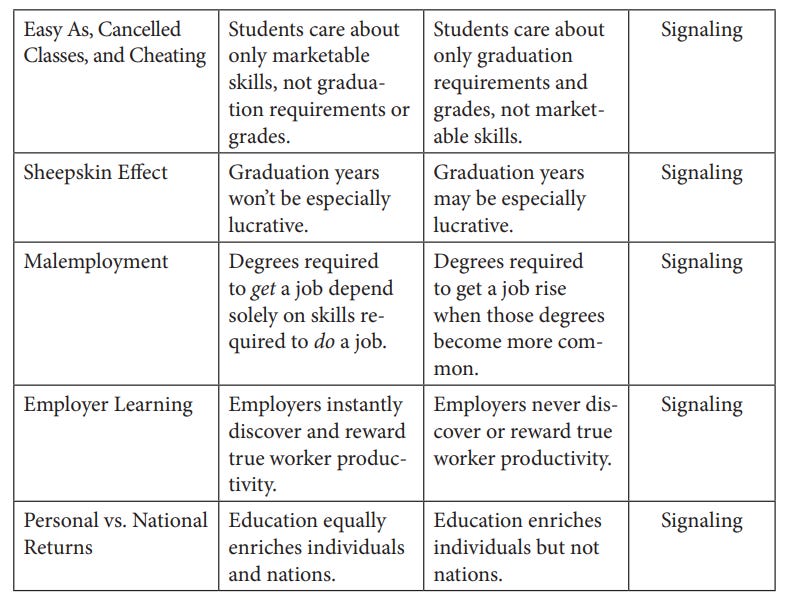

Hereditarianism also predicts that returns to education are largely due to signalling instead of improvements to ability — this appears to be the case, according to Caplan’s The Case Against Education. Properly making the case for this in an unrelated article is impossible, so I will simply post his summary:

There are a few social interventions that seem promising: divorce cooling off laws, intense tutoring, and nudging. Besides that, the rule is no efficacy.

III.

Back to the topic of hereditarianism and politics.

Let me be clear: it would be delusional to think that what I described earlier does not have massive policy implications. Based on the lottery and family confounding studies, redistribution is likely to have no effect on criminality and mental well-being. Increasing the educational attainment of children will increase their earnings, but this is largely because degrees signal ability, not because the education system is improving their abilities.

Some simple policy proposals based on these claims:

No economic redistribution. Income has a small or null effect on mental well-being, does not affect the criminality of children, and income inequality is not associated with social ill between countries

Set funding for social interventions to zero.

Make graduating from high schools and universities much more difficult, and make SAT/ACT scores public.

While hereditarianism may theoretically have massive political implications, that doesn’t mean that the public will agree.