MBTI: explained

Models of personality: part 1

Highlights:

The MBTI categorises people according to whether they have a preference for introversion or extraversion, intuition or sensing, thinking or feeling, and judging or perceiving. These four trait preferences interact to form 16 types (e.g. INTJ, ESFP).

Within the American population, 60% are extraverts, 75% are sensors, 50% are thinkers, and 55% are judgers1.

Occupaional self-selection is downstream of MBTI type.

Criticisms of the MBTI model fall apart fairly easily.

Introduction

It started as philosophy. Jung conceptualised people in terms of whether they preferred to use sensing, which is to directly draw information from memory or the senses (e.g. to see a bear running to you); and intuition, which is to make inferences based on raw information (e.g. the bear running towards you wants to attack). Sensing and intuiting are called the ‘irrational functions’ because they are not judging information, but creating it.

Then, humans can prefer to use one of the two ‘rational functions’ — thinking or feeling. Thinking involves judging something according to its function or truth; feeling involves judging something according to its value (e.g. the fact the bear wants to attack you is bad). The brain cannot focus on both types of judgements at the same time, so thinkers tend to have unconscious value judgements; feelers tend to have unconscious fact judgements.

Beyond that, Jung also noticed that some people tend to be introverted, that is to say, they focus on their internal state over the external world; or extraverted, which is the tendency to do the opposite. When looking back at Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, he thought that the Apollonian was analogous to introversion; Dionysian to extraversion2.

Those four psychological functions can then interact with the introversion/extraversion dichotomy to produce the following eight functions:

Extraverted sensing: to experience the real world as it appears. Present-focused.

Introverted sensing: to draw upon experiences from memory. Past-focused.

Extraverted intuition: to intuit various interpretations of the world as it appears and hold them as alternatives.

Introverted intuition: to focus on one particular interpretation of the world.

Extraverted thinking: to judge things according to whether they function.

Introverted thinking: to judge things according to whether they are true.

Extraverted feeling: to judge things according to whether they preserve social harmony.

Introverted feeling: to judge things according to whether they are are subjectively valued.

Some clarifications: introverts can be sociable, extraverts can be withdrawn, intuitives can live in the moment, sensors can make inferences, thinkers have feelings, feelers have thoughts, judgers can improvise, and perceivers can plan. All people have access to all eight of the functions. The MBTI is describing preferences, which are acted on when situations are flexible and people can choose to apply their function of choice.

Katherine Briggs and her daughter Myers Briggs built upon Jung’s work in Psychological Types to create the Myers-Briggs type indicator. This involved adding the judging vs perceiving preference, which corresponds to whether somebody prefers to externalise judgements or internalise them. That is to say, judgers prefer to use the extraverted feeling and thinking functions; perceivers prefer to use the introverted feeling and thinking functions.

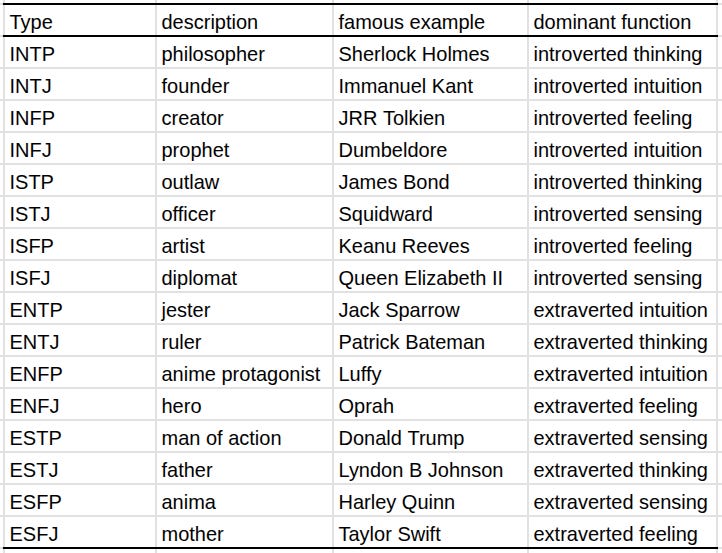

All four of these trait preferences then combine into 16 personality types:

I like using examples of famous people or fictional characters to describe the types, because it shows what each type tends to look like when they are highly successful or actualised. However, I think that a lot of famous people (especially historical figures) are mistyped, and their image rather than substance is what usually ends up being evaluated.

Whether these preferences are stable or genetic has been debated. Myers herself thought they were moderately heritable (~50%) and stable in adulthood. I, myself, think that the heritability of MBTI type is extremely high (80+%) in adults, comparable to the heritability of ADHD or autism.

The problem with the heritability studies of personality is that they use self-reports instead of peer-reports — when self-reports of the big five are replaced with composites of peer and self reports, the heritability of big five personality traits rises from 40-50% to 75%. The heritability of the MBTI is likely to be higher because it originates in people’s lataent preferences, not behaviour or character.

Isabel Myers then took all of this theory and made the MBTI test, which she was able to administer in 1945 to college students and 1962 to a bunch of high schoolers. With time, she accumulated a lot of evidence to support her theory.

Statistics

(Reminder: I = introvert, E = extravert, N = intuitive, S = sensing, T = thinking, F = feeling, P = perceiving, J = judging). About 60% of people are extraverts, 75% are sensors, 50% are thinkers, and 55% are judgers. The big sex difference is in thinking vs feeling, where 65% of men are thinkers, and 65% of women are feelers.

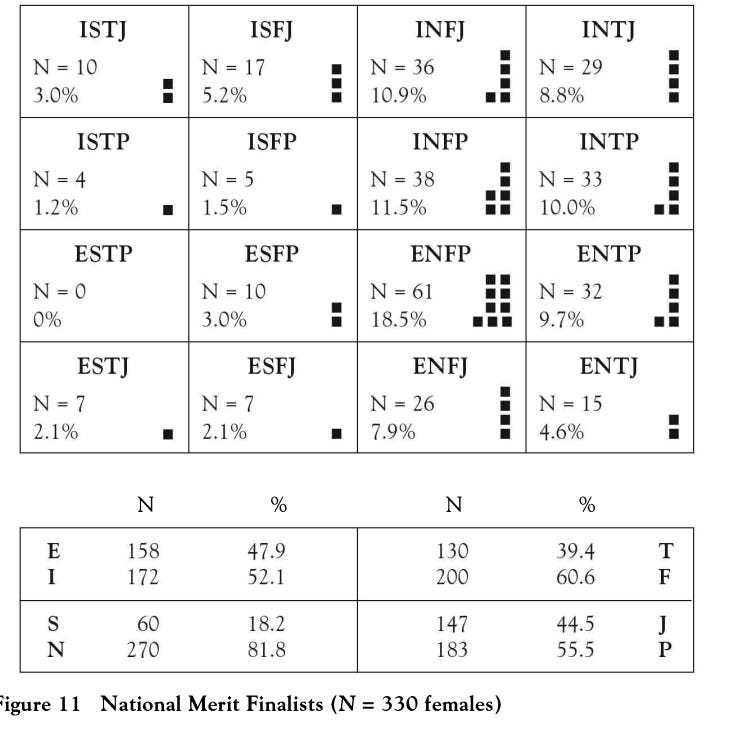

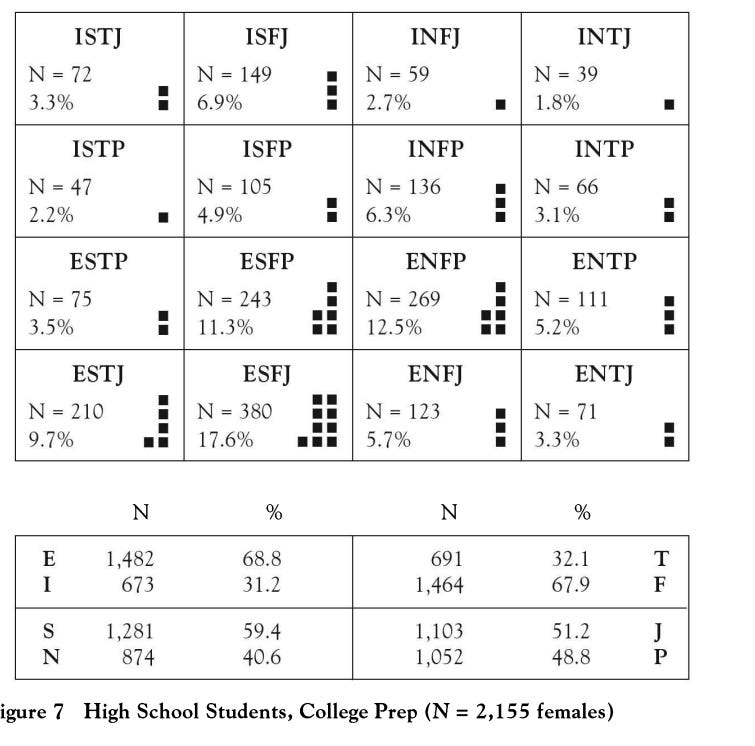

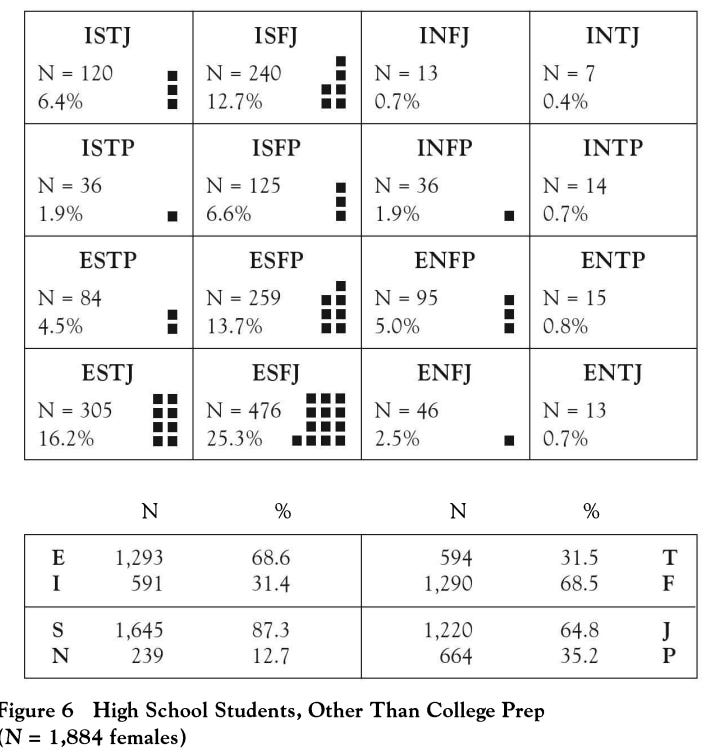

National merit finalists (top .3% in academics) are ~2x more likely to be intuitives than college prep students, who are ~3x more likely to be intuitives than regular high school students. Academic ability also seems to scale with introversion and a preference for perceiving, but not to the same extent.

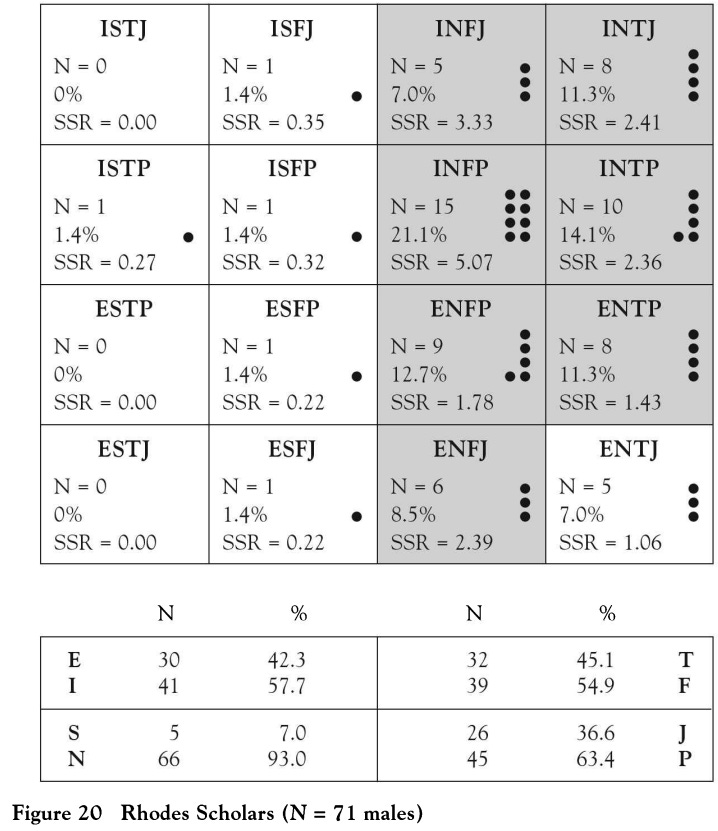

Almost all Rhodes scholars are intuitives:

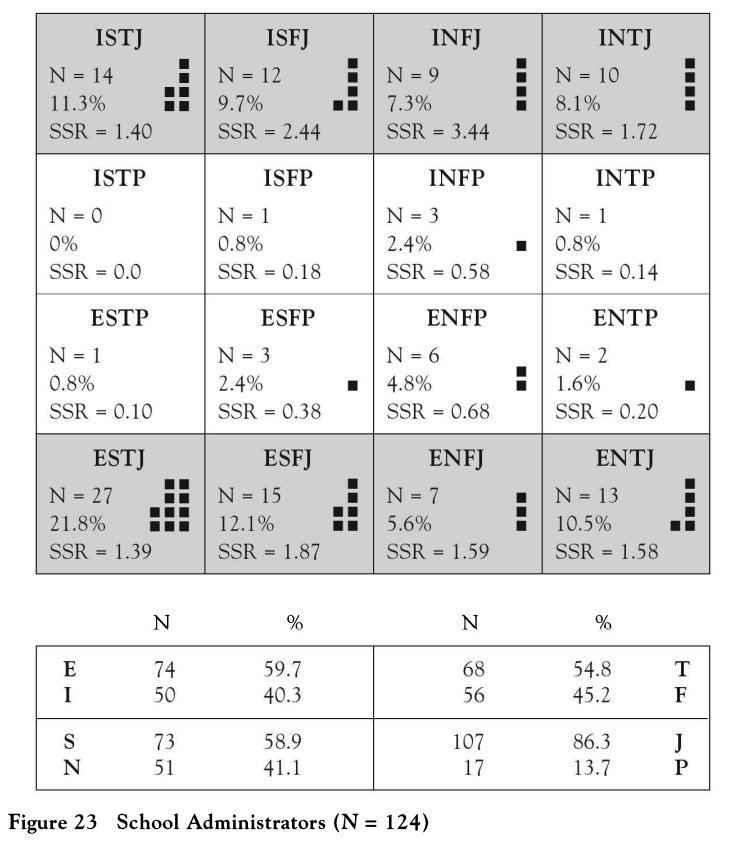

School administrators are overwhelmingly judgers:

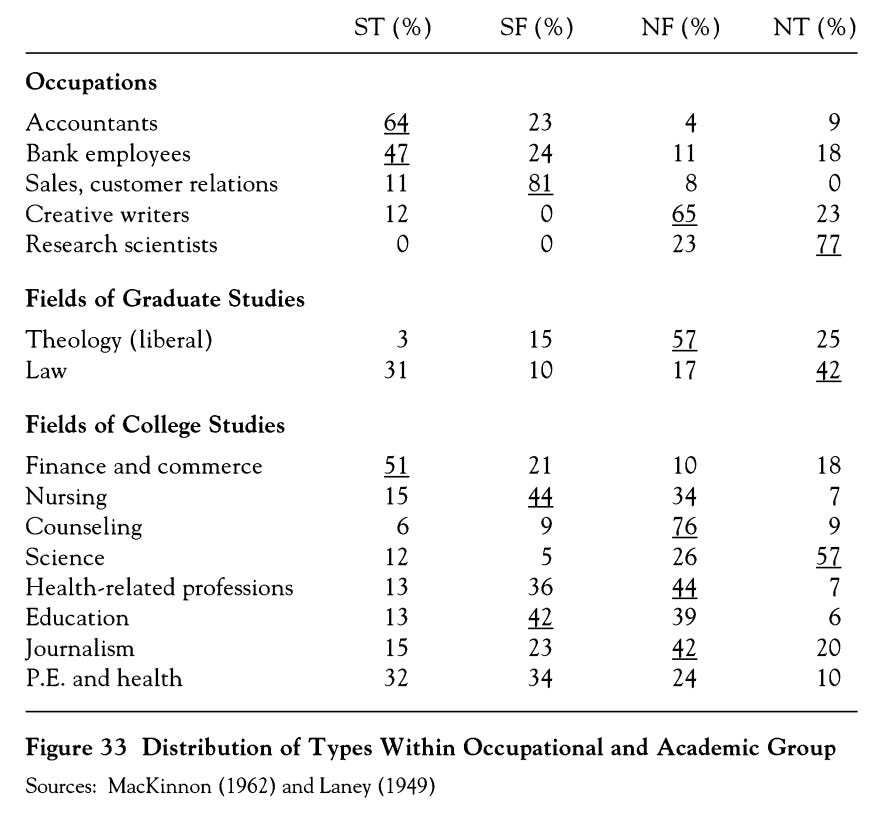

Summary of MBTI type and occupational selection:

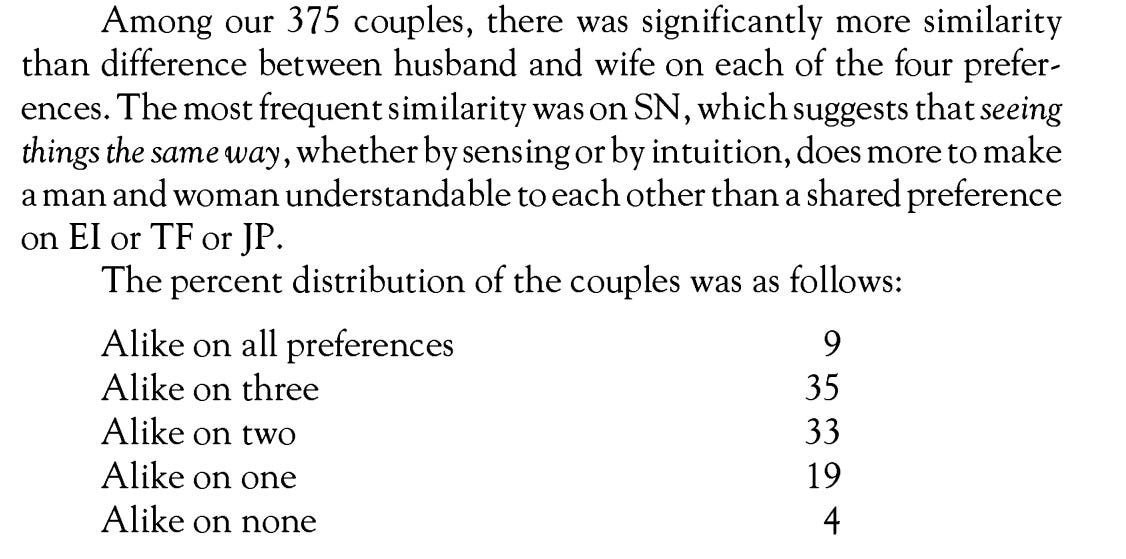

Assortative mating for MBTI personality exists, but isn’t particularly strong. Extraverts were more likely to be matched in terms of personality than introverts.

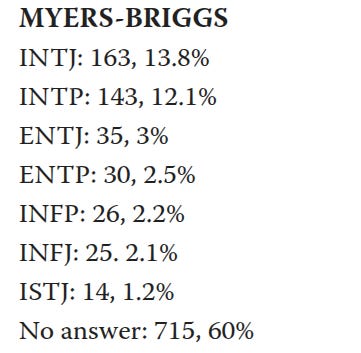

65% of Less Wrongers (rationalists) who answered their MBTI type on the site-wide survey in 2012 said they were either INTPs or INTJs. Almost all of them were intuitives.

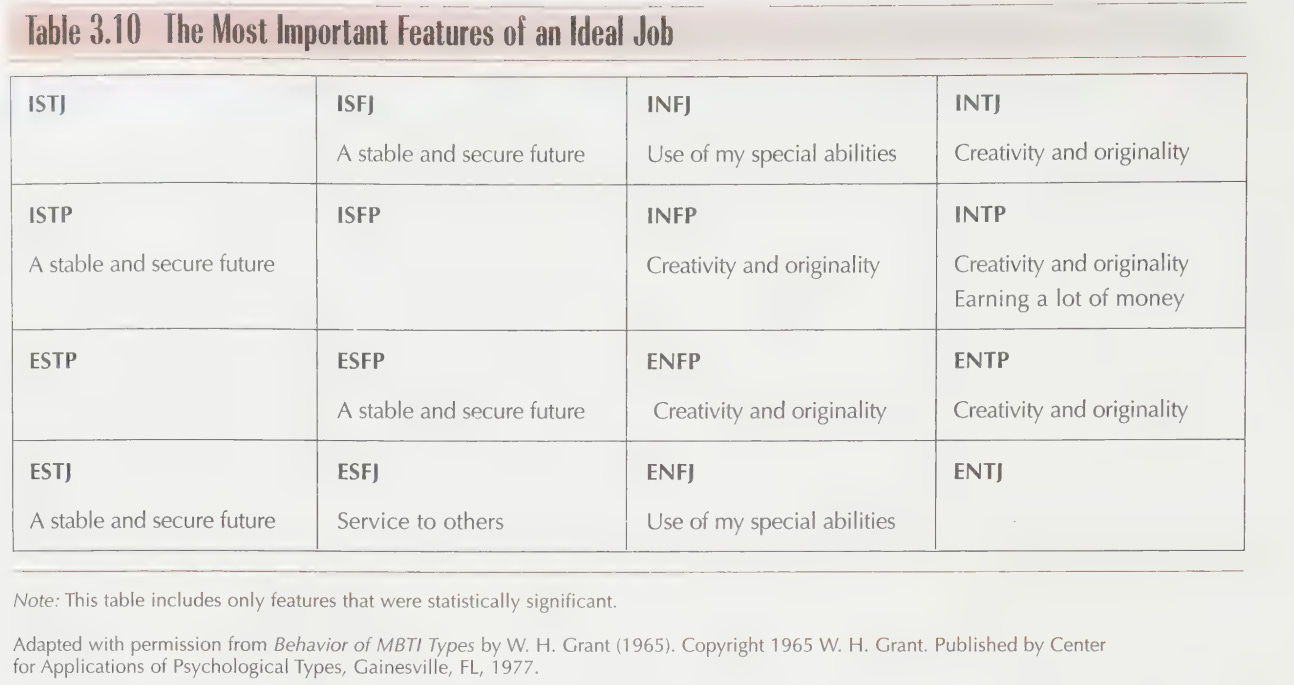

What each type wants from work. Sensors gravitate towards stability, intuitives towards creativity:

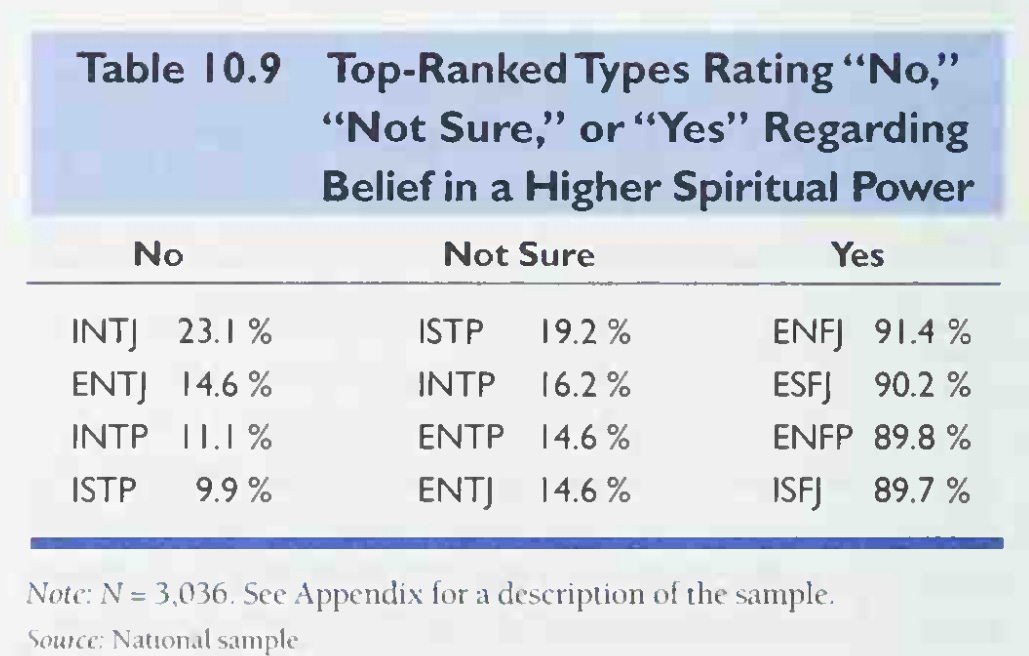

Religiosity by MBTI type3:

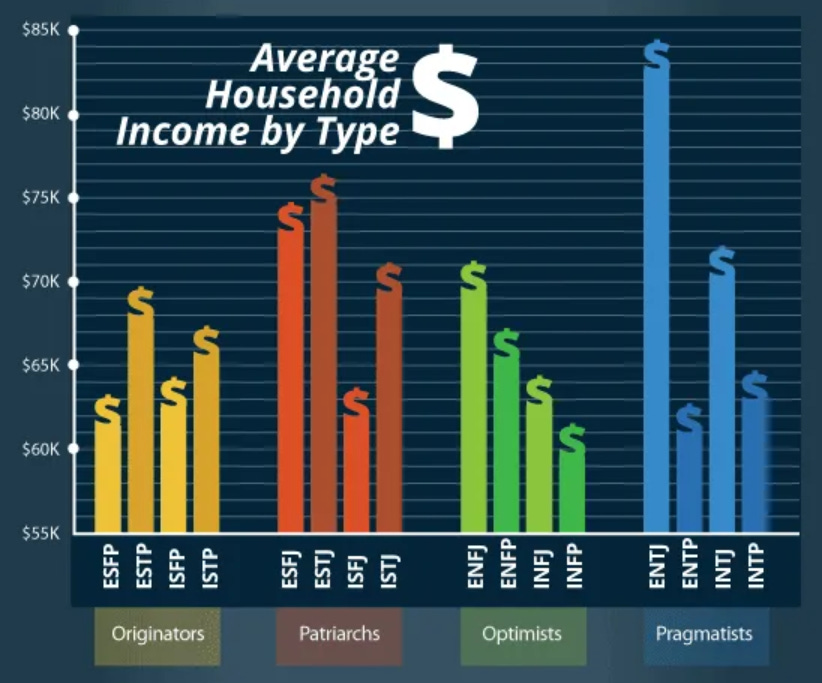

Income and MBTI type (E > I; N > S; T > F; J > P):

Trait descriptions

Type descriptions have already been done to death. What is underdone is good descriptions of each axis of preference.

It’s impossible for personality types and preferences to be equal in aggregate value, because they are, well, different. And that’s fine. I generally think that the value differences in MBTI types are small, and that some trait preferences (particularly introversion and sensing) are underrated and their utility is harder to perceive. MBTI typology is best at predicting what people select into, but not how good they are at what they do.

Myers hypothesises that the best-adjusted people are “psychologically patriotic” and are glad to be what they are, and accept it. Which makes sense, since MBTI typology is so heritable and stable, and self-actualisation must build itself on the genetic foundation rather than destroy it. From a functional perspective, an egalitarian view of the MBTI encourages people to accept who they are rather than trying to be something that doesn’t reflect their genetic destiny.

Extraversion vs introversion

At a definitional level, extraverts prefer to focus on their surroundings, introverts prefer to focus on their internal states. There are many biological parameters, values, and upstream preferences (e.g. introverts have higher baseline arousal, extraverts have higher reward sensitivity) that decide this preference, but I don’t think that those things are extraversion or introversion themselves.

Beyond that baseline, definitional description, extraverts and introverts tend to differ in the following tendencies:

Extraverts act, then think; introverts think, then act.

Extraverts are easily distracted; introverts less so.

Extraverts are relaxed and confident; introverts are typically not.

Extraverts comfortably express their emotions; introverts do not.

Extraverts comfortably engage in overt status displays or striving; introverts find this unnatural.

Extraverts suffer from a lack of substace; introverts from a lack of practicality.

Introverts are more likely to engage in substance abuse4.

Let me get the elephant of the room out of the way. Extraversion has a lot of visible advantages. They tend to have higher incomes, better social skills, romantic partners with more similar personalities to them, more friends, and are less likely to be incels. The general wisdom online is that extraversion is better than introversion. I don’t think this is the case — the advantages of extraversion are just more obvious.

The one, big advantage of introversion is that introverts are more capable of change and action independent of outcomes. If a new business is unprofitable for three years, but has evidence of promise or growth under the surface, an introvert would be more likely to stick with it than an extravert. Extraverts often have to rely on encouragement or external rewards to continue doing something, while “doing it for the sake of doing it” is an introvert thing.

By the very nature of the trait, introverts have more access to their inner world of ideas, feelings, and thoughts, which allows them more self-aware and metacognitive. A rather unexplored area of research is that, by virtue of having more reliable access to their own feelings and ideas, that perhaps introverts give more accurate responses on surveys, and that this distorts observed statistical relationships.

Defenders of introversion, in my opinion, have relied too much on Susan Cain’s ideas. In Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, Cain argues that introverts are systematically oppressed in the modern world and that the ideal person is an extravert — charismatic, high energy, and persuasive. I don’t disagree (or agree, necessarily) with what she says on an object level, but the grievance-based approach is undignified. It’s not surprising that the environment rewards those who love the environment more.

Intuition vs sensing

Intuition is a tendency towards making inferences and intuitive leaps from a given set of base information (be it memories, sensory data, or even ideas), while sensing is a preference for focusing on the base information itself. Intuitves are more likely to trust their intuitions and engage with them, sensors not so much. Most people are sensors, especially beyond the developed world. In terms of tendencies:

Intuitives have higher levels of risk tolerance in abstract domains, sensors have higher risk tolerance in physical domains.

Intuitives are more likely to skip steps in processes if they view them as obvious or trivial5, while sensors are likely to do things by the book.

Sensors are naturally observant and attentive to details, intuitives are only observant and attentive insomuch as they relate to their ideas and inspirations.

Sensors have more consistent and diligent work habits, intutives are more likely to work in bursts.

Sensors often engage in frivolous behaviour if not balanced by their judging processes, intuitives struggle with being fickle and impersistent if they do not properly judge the world.

Sensors are more likely to be religious.

Statistically, the elephant in the room with intuition vs sensing is IQ — intuitives score about seven IQ points higher than sensors6. The vast majority of people in the top 1% of cognitive ability are intuitives.

People have various theories as to why this is. Myers thinks that a big problem is test bias, where IQ tests reward people who are willing to make far-reaching, abstract judgements from a limited set of information. And that’s the bread and butter of intuitives. She highlights some examples of sensors who scored higher on tests by rushing through tests faster and with more confidence in Gifts Differing, which seem genuine, but I wouldn’t put much more stock in them beyond the average anecdote.

I think this is probably true to some extent, but the problem I see is that people need to make abstract judgements in real life too, so it’s not a test-specific skill. A lot of IQ subtests also do not involve abstract reasoning, they involve doing a bunch of simple things really quickly (like the symbol search subtest in the WAIS), or remembering a set of digits. These involve no abstraction at all; I would be interested to see if intuitives are still advantaged on these subtests as well.

What I actually believe in terms of the IQ difference is that it is functional pleiotropy. The more intelligent the intelligent person, the easier it is to judge farther reaching and complex intuitive leaps. The ease of the process creates the preference, not the other way around. That said, there is nothing wrong with a preference for sensing — failing at the intuitive level is much, much easier than failing at the sensory level.

Thinking vs feeling

This is a visible dimension in terms of it being easy to intuit and it being frequently discussed. Definitionally, thinking concerns itself with relating things to other things, and feeling concerns itself with what things are valued. In terms of tendencies:

Thinkers have more unconscious feelings, feelers have more unconscious thoughts.

Thinkers have lower levels of agreeableness than feelers.

Feelers have better social skills than thinkers, particularly when it comes to understanding social norms and other people’s emotions.

Contrary to popular belief, thinkers do not have higher levels of cognitive ability than feelers. If anything, outlier high IQ people are slightly shifted towards feeling.

Feelers are more likely to be religious.

Thinkers are more likely to struggle with human relationships, less with jobs.

This difference is pretty straightforward. The only thing I need to elaborate on is the “decoupling” idea, that some people can separate truth and value — and that perhaps this is consistent with a preference for thinking over feeling. I reject this. Facts and values are conceptually distinct, but ultimately part of the same system. Focusing on the facts causes the valuation process to retreat to the unconscious, focusing on values forces thoughts into the unconscious.

Judging vs perceiving

People often confuse this with the “conscientiousness” facet of the big five. It’s not the same thing. Judgers prefer structure while conscientious people are better at executing it. Concretely speaking: judgers prefer closure and external structure; perceivers prefer internal structure and the ability to keep options open. In terms of tendencies:

Judgers are more opinionated than perceivers, who have either absent, developing, or uncertain opinions.

Judgers often decide on a best way of doing something and always do it that way, while perceivers do whatever feels natural.

Judgers find local maxima and optimise them, perceivers try to search for the global maxima… And often fail. Sometimes, they don’t.

Perceivers are natural deconstructers, judgers are natural builders.

Perceivers hate missing information, judgers hate leaving it unexamined.

Judgers are more comfortable forcing the world to comply with their standards, perceivers are better at accepting it as it is.

Judgers with bad perception are rigid and incapable of tolerating other people’s perspectives, perceivers with bad judgement devolve into laziness

Judgers are more likely to be religious.

I think the judging/perceiving difference is the hardest to evaluate in yourself, because there is often a gap between what you think you should do, what you naturally do, and what you do in a given moment. People who naturally prefer external structure, but aren’t good at implementing it, it might look like perceivers; their preference is judging.

Jungian functions

This is where MBTI theory starts to become much more abstract, unfalsifiable, but interesting. Beyond the four preferences, MBTI also theorises that there are eight type functions, which Myers and Briggs took from Jung. A quick rehash:

Extraverted sensing (Se): to experience the real world as it appears. Present-focused.

Introverted sensing (Si): to draw upon experiences from memory. Past-focused.

Extraverted intuition (Ne): to intuit various interpretations of the world as it appears and hold them as alternatives.

Introverted intuition (Ni): to focus on one particular interpretation of the world.

Extraverted thinking (Te): to judge things according to whether they function.

Introverted thinking (Ti): to judge things according to whether they are true.

Extraverted feeling (Fe): to judge things according to whether they preserve social harmony.

Introverted feeling (Fi): to judge things according to whether they are are subjectively valued.

Myers and Briggs theorise that a type’s dominant function is determined the following way. First, they have their irrational (S vs N) and rational (T vs F) preferences. Then, the judging vs perceiving trait (J vs P) decides whether the main rational function is internal or external. If it is perceiving, it is internal; if it is juding, it is external. The main irrational function works the opposite way: if a person is judging, then their main irrational function is internal; it they are perceiving, it is external.

Introversion vs extraversion decides which of the two main functions dominate — sorting them into a ‘dominant’ and ‘auxiliary’ function. Then, the inferior functions (the opposites of the dominant functions) balance out the dominant functions. Use of only introverted functions leads to solipsism, use of extraverted functions leads to meaningless reactivity. And it also can’t be a judging function too: all judgements and no perceptions leads to nowhere. So if the dominant function is judging, then the auxiliary function is perceiving and vice versa.

Allow me to be more concrete. Let us take my personality type (INTP7) and infer its function hierarchy. The P means that the thinking is internal, and the intuition is external. The I means that the introverted function dominantes the extraverted one. So, we have Ti > Ne. The opposite functions then have to balance out the dominant ones, so then we have Ti > Ne > Si > Fe. Ti is the dominant function, Ne is the auxiliary, Si is the teritary, and Fe is the inferior.

The dominance does not mean that the function is more developed, but in practice, it tends to happen that way — INTPs naturally prefer Ti and Ne, so they develop their execution more completely. On the other hand, Si and Fe are not as developed and focused on, so they retreat into the unconscious. As such, INTPs often struggle from repeating the same mistakes and misplacing things (Si deficits) as well as awkwardness and emotional, validation seeking outbursts (Fe deficit). That… describes me better than I would like to admit.

Essentially, in MBTI, personality development happens by accepting your preferences, and then trying to develop the execution of your inferior functions first; then awareness of your shadow functions if you can.

The logic of which function dominates does make sense and follows cleanly from basic MBTI theory, but the part about the inferior functions balancing out the dominant ones… I don’t really know if that is true.

Traditionally, it has been posited that the dominant emerged in childhood, the auxiliary emerged in teenage years, the teritary emerged in adulthood, and the inferior was almost always never fully developed. Now, people are more skeptical of this, and are not as sure about whether function maturation is the same for all people. I, personally, doubt it.

Criticisms of the MBTI

The most common criticism of the MBTI is that it is not scientific. Scientific… Meaning what? Does it have institutional approval? Is it official? Is it high status? Is it able to systematically make testable hypotheses about the physical world? The answers to the respective questions are: it depends on the insitution, kind of, not really, and yes. It is commonly believed that scientific experts reject the MBTI, when, to my knowledge, there is no survey of expert psychologists’ opinion on the model.

So yes, the MBTI is about as “scientific” as any psychological theory, like IQ or the big five. It’s not scientific in the sense that it involves a lot of abstact constructs, but if you take the constructs for granted, then testing said constructs are the same as testing any other physical thing, like the weight of a human. There is some abstraction and faith that goes into the concept of a body itself, but it is not as big of a leap.

People also criticise it for dichotomising its variables, which reduces their reliability and granularity. This critique is rather confusing, because the point of the MBTI is the dichotomisation and trying to model humans using how different preferences interact to produce different archetypes. And MBTI tests can give continuous scores as well, they just aren’t as commonly used.

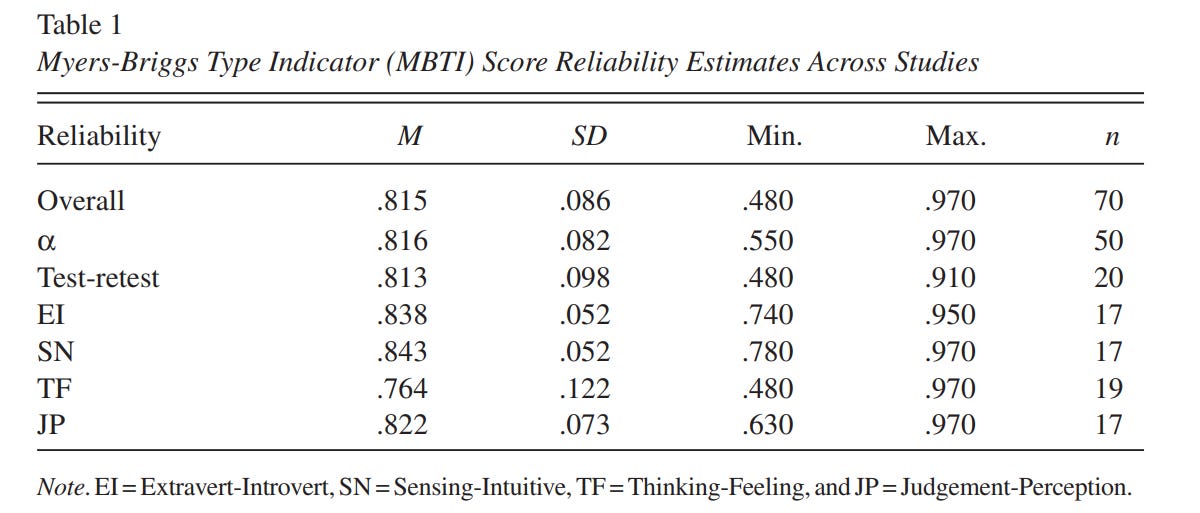

People have criticised the MBTI test for being unreliable, sometimes based on a single statistic, or on anecdotes. So, to be clear, let us assume the test is reliable. Does that mean it is good? No — if the thinking/feeling test was simply a bunch of questions asking “do you like computers” with different wording, then it would be bad. And if the test was unreliable, then that wouldn’t mean that the MBTI framework itself is bad, it could just indicate the test is in need of improvement.

So, the “MBTI is unreliable” critique proves itself to be uninteresting. And for those who are interested in it, the official MBTI test’s reliability is within the standards of the statistical community, which is > .70. The dichotomisation makes the statistical unreliability more apparent.

Myers in Gifts Differing noticed issues with the reliability of the MBTI test in children and teenagers, and she attributed this to their preferences not being as defined or developed at a young age; I would also note that self-awareness and self-concept scale with age. So the actual MBTI test being unreliable might not even be an issue with the test or the framework, it could be the nature of the testing circumstance.

The main functional shortcoming of the MBTI, in my opinion, have to do with poorly modelling emotions and actions — it’s missing something along the lines of order/self-efficacy and emotional attachment/neuroticism. In terms of praxis, I also think the MBTI leans too much into institutionalism by having a “main MBTI organisation”, perhaps if there was no official MBTI, then people would be more comfortable researching the model.

Further reading

Gifts Differing — Isabel Myers

Psychological Types — Jung

MBTI manual (v3) — Isabel Myers

The distribution of MBTI types is definitely something that needs to be ironed out more, because the line in the sand that denotes whether a person has a given preference is arbitrary. I do think, however, that the distribution I cited (based on the samples of school students in Gifts Differing) are close to the truth.

I’d say Dionysian vs apollonian is more consistent with dynamic vs static in the unrotated big five, but introversion/extraversion is pretty close.

Source: the MBTI manual. Basically every single introverted type is more likely to abuse substances, even the judgers. I think this is because what attracts people to drug abuse is internal, and what they do to your experience, not social.

I do this all of the time, much to the annoyance of my colleagues and teachers.

source: Gifts Differing by Isabel Myers

Guesses for percentiles: introversion: 5th percentile; intuition: 99+th percentile; thinking: 60th percentile; perceiving: 65th percentile.

This is a really nice article, and expresses a lot of things I've dwelled on myself.

On test reliability: I've long had a pet theory that the T-F and J-P axes are much less reliable than the other two. From personal experience, I've taken the 16Personalities test (and similar MBTI tests) several times in the past ten years, and I've never once scored outside the IN box; but I scored INTJ as a young teen, INFP just a moment ago. The reliability stats you give seem to support this theory for the T-F, but not really for the J-P, so idk. (Relatedly: Maybe people are just relatively worse at assessing their T-F and J-P? There's definitely a social pressure to exaggerate conscientousness and adjacent traits in one's self reports, and I imagine that for men there's motivation to downplay how "emotional" one is.)

Also, you mention that "If anything, outlier high IQ people are slightly shifted towards feeling". I was wondering why you think that is? Any specific examples?

MBTI has significant correlation to Big 5, so its lesser validity is likely primarily due to this. The basic MBTI is more popular, likely because typical people prefer the typological and strengths-weaknesses/equal value framing.

https://www.clearerthinking.org/post/how-accurate-are-popular-personality-test-frameworks-at-predicting-life-outcomes-a-detailed-investi

The J/P dichotomy mixes conscientiousness (like being orderly, as a strength) with being closed (like being closed to new information or options, as a weakness), versus being unconscientious with being open. Disorganized, unplanned and unadaptable, unambiguous people obviously, commonly exist, but that is socially undesirable.

As a complement to Big 5, more men should be classified as disagreeable (Big 5) feelers (cognitive type), not thinkers. They primarily process information through a lens of valuations that are simply more competitive and individualistic. This includes their feeling identification as “thinkers.”

Both of these dichotomies have weaker Big 5 correlations and are philosophically weak. I think personality typology has something more to offer, which people are far less aware of, but not where it overlaps with Big 5.